The future of this new age of American spirituality rests on the ability of all parties to enter the conversation with an ability to get to the bottom of the issue of Christian-suitability of CAM practices without further accusations of heresy, faddism, or appropriation. Instead, the CAM mechanism of action ought to get critiqued without further attempts to use the argument of authority to silence dissenters of the church. Likewise, perennial thinkers must let go of the illogical fallacy that all truths can be equally valid. Murder cannot be okay for some people and not for others. Given the intersection of psychology and religion, it is instead time to embrace a conversation that involves a firm commitment to critical thinking. Furthermore, evangelical and conservative voices are needed in the conversation to engage those who disagree with them from a place of humility while still holding to sound doctrine as the basis for rejecting the illogical fallacy of religious multiplicity.

Arguments For and Against Christian Complementary Therapies

It appears that perhaps the very nature of yoga’s complexity is designed to challenge the fundamental religiosity of any world religion by its elusive nature. Yoga as a system seems to elude traditional systematic theology, which seeks to protect discerning Christians from potential theological errors. Van Ness (1999) placed yoga’s roots in ancient India before the Vedic era more than 2000 years ago. He stated that it had informed some Hindu and Buddhist institutions. Yoga gets defined as a disciplined practice that can be spiritual or secular. He contended that it does not have to be devotional (Van Ness, 1999).

CAM: Is It a Fad or Heresy? Klassen (2005) reported a growing trend of liberal Christians who borrow Asian healing-related practices such as yoga, Buddhist meditation, and Reiki. These Christian pastors and practitioners often use such methods in a web of Christian rituals. These types of Christians get criticized for their syncretism. Other Christians tend to charge them with heresy. She asserted that colonialism and Christian missionaries had paved the way for religious borrowing and appropriation. Opponents of Christian Asian-adapted practices often have xenophobia and the need for an “other” to oppose. They refuse to acknowledge how Christianity was shaped by culture and mysticisms from other cultures (Klassen, 2005).

Most who judge CAM do so on the moral precept that pluralistic healing is a fad or heresy. Critics attempt to devalue spiritual seekers as shallow consumerists rather than as legitimate practitioners. In this regard, some Hindu-nationalist condemns the Christian adaption of CAM due to the religion’s past of predatory imperialism and appropriation. Those who police perceived heretics usually have a power imbalance in which they falsely assume to be higher-appointed guardians of the doctrines and truth of their religion (Jain, 2013). Often, the heart of this argument is between liberal and conservative Christians (Klassen, 2005). Prana is spirit, which makes sense that these practices are, therefore, spiritual. Our spirit, or the breath of life, is innate to all beings regardless of religious affiliation.

Yoga Is Simply Exercise. Some Christians contend that yoga is simply breathing and stretching. Still, Smith et al. (2011) conducted a study that found that yoga practiced in an integrated spiritual form produced more benefits than yoga practice for exercise. They discovered that yoga created benefits beyond a control group. They recommend further research into the crossroads of a Judeo-Christian worldview with the tenets of yoga. They encouraged the use of bhakti passages in meditation instead of Eastern concepts to enhance spirituality for Westerners in alignment with their worldviews (Smith et al., 2011).

Christian Yoga. Corigliano (2017) placed Christian yoga within the realm of devotional or bhakti-yoga. This type of yoga focused on the development of a personal relationship with God. She encouraged Christian yoga to emphasize a dialectical relationship between technique and religious affiliation prevalent in Hindu approaches to yoga. Corigliano (2017) asserted that Christians have long been appropriating Hindu practices. She defines Christian yoga as a spirituality that blends some yoga philosophy with the ideals of Christianity with a distinct focus on Jesus as the hope of salvation.

Corigliano (2017) breaks Christian yoga into three categories:

- The first is the people who combine yoga with Christianity without much concern for orthodoxy and tradition. They usually create a new type of religious community.

- The second are those that attempt to adopt Christian ideas into Hindu religious values in Yogananda’s kriya yoga vein. This approach is more of an attempt to view Jesus through the lens of yoga.

- The third is a movement of Christians who use yoga to enrich their Christian faith with respect to orthodoxy. They use yoga as a tool to deepen their spiritual life

in hopes of attaining communion with God.

Some argue that Christians can do yoga based on the premise that the elements of yoga have been present in Christian contemplative traditions all along. These practitioners identify lifeforce as the Holy Spirit. They view meditation as a means of bringing more awareness to the Holy Spirit. They also believe that yoga is primarily a philosophical system used as a supplement to other spiritual practices. They acknowledge meditation as the primary goal of yoga (Corigliano, 2017).

Corigliano (2017) further pointed out that the divination of humanity is a biblical concept as humans are made in the image of God and can, therefore, experience the likeness of God as the sons of the Son. Yoga, in this sense, is a transformation of consciousness to understand what it means to be sons of God in a subservient way to God. Generally, Christian practitioners of yoga agree that yoga is used regardless of religious boundaries as they all define yoga as a union with God. This idea contrasts with Hindu practitioners of yoga who tolerate other religions yet view Hinduism as Santana dharma or the most superior path to God. In essence, Hinduism views its various gods as a reflection of the one God. The ultimate truth is that we are that God (Corigliano, 2017).

Furthermore, Corigliano (2017) stated that Christian practitioners tend to believe that householders should practice yoga instead of just in ashrams. These are people who have jobs and families. Therefore, yoga can and should start as an attempt to refine the body and mind. The spiritual or religious parts of yoga only come into play during later aspects of the practice. This freedom from religious dogma makes adhering to yoga practices for devotion ambitious for non-Hindu practitioners (Corigliano, 2017).

Problem Statement

The problem is that there appears to be a lack of consensus in the literature regarding the suitability of complementary therapies in the context of Christian healing ministry. There also appear to be two unrelated emerging themes in the literature to date. The first is the growing body of empirical evidence regarding the clinical utility of incorporating complementary therapies into complex and familial trauma treatment. This entire realm of psychology fails to adequately accept and address the complex implications of the spirituality and religion innate in these modalities. The third and fourth waves of psychology are arriving at a growing acceptance of the role of spirituality within the context of mental and emotional healing. In addition, there are genuine considerations regarding the legalities of the scope of practice laws that also give rise to academic and professional integrity.

The second emerging problem is the intersection of psychology and religion in the form of spirituality. Psychology formerly avoided religion and now wants to reclaim spirituality as an essential catalyst for emotional healing. Likewise, faith is borrowing from psychology to address the needs of hurting individuals. Both camps have had different claims to owning the right to facilitate healing. The tension becomes evident in the scope of practice laws that seek to protect vulnerable people from predators that seek to bestow harm. Currently, they are running out of bandwidth to denounce or ignore one another. The fields of transpersonal psychology and pastoral counseling would be wise to set aside their theological differences for the shared purpose of bringing their voices to the conversation regarding the evolution of Western spirituality.

Wright (2006) described an interfaith concept termed the law of prayer which supports the assertion that intercessory prayer can be effective regardless of which religion a person claims to follow. This process includes prayer as a catalyst for contemplation and meditation which results in the union between the person and God that parallels the Buddhist concept of no-self or enlightenment. The intercessor submits their will to God’s will and is thereby transformed. It also correlates to the subjective awareness process known as consciousness. It appears that this law of prayer is available to all humanity as a form of common grace that can either be adhered to or not.

It appears that salvation is Christ’s payment for the karmic cost of sin present in the human condition, available to those who accept this payment through a reconciliation of the misuse of humanity’s free will. Whereas, enlightenment, or union with God, appears to be a process of reuniting with God by overcoming the illusion of separateness between us and God. In a Christian worldview, one comes to realize their identity as children of God alongside the implications of being made in his image. This contrasts with a Hindu belief that one is God or a Buddhist belief that there is no God. Regardless of religion, reconciliation through enlightenment appears to be available to all through these tools of contemplation and meditation.

Furthermore, Pentecostal lay-healing ministers and new-age spiritual practitioners share more in common than either party care to admit, as evidenced by their shared historical development over the past 100 years in America. Both groups become disillusioned with medicine and religion in different ways. However, their ability to have the hard conversations regarding Christian spirituality could have monumental implications, especially for conservative evangelical pastors hoping to maintain a voice in this needed conversation. Moreover, fundamentalists must stop appealing to the argument of their authority in the church to defame Christian practitioners of CAM as heretics as a means to avoid the hard conversations.

From this place of open-hearted and academically sound dialogue, a new wave of Christian spirituality can emerge. This group will balance an unwavering commitment to academic, scientific, and theological integrity with an open mind toward the mystical realities of complementary therapies. Suppose pastoral counselors can Christian-adapt CAM the same way Christmas and Easter have been historically Christian-adapted. In that case, pastoral counselors could be at the forefront of a new wave of emotional and spiritual healing. Furthermore, the church could have a much more powerful family and inner healing reach if it accepted the emerging reality that the clinical benefits of CAM modalities are indeed far outweighing the theological concerns of fundamentalists. It is now time for the fields of transpersonal psychology and pastoral counseling to engage one another for the shared purpose of catalyzing individual and family healing through spiritual means with all the complexities involved in that process.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this study is to develop a working theory of Christian-adaptable complementary therapies for familial trauma. The goal is to both refute extremist viewpoints regarding CTs by addressing the mechanism of action and support the emerging need for Christian-adaption of CTs. I also explored what the research says about Christians practicing alternative medicine as a core part of the study. Although ministry could include clinical counseling, a big part of the gap I have identified is the lack of intersection between trauma, complementary therapies, and Christian ministry. An abundance of research exists on the efficacy of complementary therapies on trauma. I also noted some conversations regarding the issues of Christians practicing alternative medicine. The gap exists regarding where Christian ministry intersects with complementary therapies for trauma. I have also identified Christian ministry as a type of complementary therapy. Moreover, Pentecostal inner healing prayer would be considered alternative medicine, and Christian lay ministers practice under the same legal scope of practice umbrella as yoga teachers, massage therapists, and Reiki practitioners.

Significance of the Study

This study seeks to address the problem of whether or not it is appropriate for Christians to adapt CTs by clarifying a basic understanding of what the existing research says is suspect. Although it was not exhaustive, the goal was to provide insights regarding how Christian practitioners might better engage the sensitive topics of Christian CTs for familial trauma. This study provided researchers with needed direction regarding how to better address the theological and clinical complexity of whether and how Christians can adopt CTs into the third wave of behavioral therapy. Specifically, this study hopes to address the oxymoron of Christian mindfulness by focusing on the mechanism of action in meditation. If this can be determined, researchers will be equipped with better insights regarding how and what theologically is and is not appropriate for integration by Christian practitioners. These insights can be applied to a wide range of biofield and meditation-based CTs aimed toward healing. It also provided needed consensus regarding what needs to be adapted, what cannot be adapted, and why it should or should not be adapted by Christians. Finally, although there will continue to be complex debates regarding the appropriateness of CAM for Christians, this helped discern whether the theological risks are worth the clinical effectiveness when it comes to treating familial trauma.

The student author proposes that CTs (including Christian lay-ministry) will emerge as effective treatments for healing familial and relational trauma. The student author also suggests that lay ministers, CT practitioners, and clients will significantly benefit from having direct access to CT’s research findings that appeal to a logic higher than appeal to authority. Finally, an increased understanding of the impact of family trauma in healing ministry will streamline treatment efforts and reduce the cost of highly specialized mental-health training.

The study’s objective was to discover what the research says about the place of CTs in the role of family healing ministry. They attempted to create a working theory of Christian-adaptable CTs for family healing ministry grounded in the research. Furthermore, the findings will help Christians sort through alternative medicine’s cultural and religious baggage to clarify the underlying mechanism of action. The goal is to help Christians understand what needs adapting while promoting evidence-based methods of alternative healing methods. Another goal is to help lay ministers clarify their role in ministry to help families in pain.

This study addressed Christian-based complementary therapies in lieu of Buddhist-inspired mindfulness practices. This is because a large majority of Americans are Christian, and Buddhist-Christianity is an oxymoron like Christian-atheism. K. Ford and Garzon (2017) explained that the majority of third-wave therapies currently being studied are based on Buddhist-inspired mindfulness. Knabb, Johnson, et al. (2020) further described the need to identify a completely different purpose for Christian meditation. They recommend Christian-sensitive versions of meditation in lieu of simply adapting mindfulness for Christians. This is a large gap in the research I hope to address by focusing on the Christian component of complementary therapies.

Research Questions

The primary research question (RQ) is: Are complementary therapies Christian adaptable and indicated when ministering to adult survivors of familial trauma?

This question has four sub-questions contained within the larger question:

- RQ1: What is the mechanism of action that underlies CTs?

- RQ2: Do the theological risks of CTs outweigh the perceived benefits in

ministering to adult survivors of familial trauma? - RQ3: How are CTs implicated in supporting mental health and trauma

when used in Christian ministry? - RQ4: How do CTs need to be adapted for Christian use?

The student author further proposes that CTs emerge as Christian-adaptable, with the benefits outweighing theological concerns for use in lay ministry. Furthermore, the student author suggests to embrace CTs with certain Christian caveats could prove vital to catalyzing a new age of Christian spirituality through refined consciousness, mind-body awareness, and increased attunement to the Holy Spirit. This study hopes to identify a definite gap in the literature without quantifying direct cause and effect. A meta-synthesis would most appropriately explore a large body of research to narrow down this specific gap. This working theory would emerge as a result of science instead of the personal opinions of a particular author. In addition, it alleviates the element of proof-texting biblical passages to construe the Bible into supporting a single pastor’s theological position. It also eliminates the power dynamic of a professor or pastor using their knowledge of the Bible or position of authority as grounds to build an argument. Likewise, it pulls the argument out of the realm of clinical mental health. Although mental health is considered, the pastor’s role is integrated into the spiritual realm of CTs as a central part of the conversation. This shift moves the argument out of its current standstill of opinion based on anyone pastor’s knowledge of the Bible or academic clout and into the hands of the research.

I included a discussion of pertinent biblical passages, but the argument was mediated by something higher than the moderating of the pastors of modern American evangelicalism. This argument is an appeal to authority in critical thinking, and it is an invalid argument in this case.

Definitions

- Familial Trauma—A broad range of complex trauma occurs in family systems and includes betrayal, attachment, complex, developmental, and intergenerational trauma (Isobel et al., 2019).

- Family Systems Theory—A range of family theories rooted primarily in Bowenian and Minuchian marriage and family therapy theory (Tan, 2011).

- Christian Spirituality—An evolving Christian spirituality emphasizes complementary therapies and contemplative sciences as a central part of one’s union with God (Bidwell, 2001).

- Christian Adaptable—A term used to delineate Christian-appropriate alternative medicine and mindfulness practices (Garzon & Ford, 2016).

- Transpersonal Psychology—The fourth wave of psychology theory embraces spirituality as a central part of the human healing process (Siegel, 2018).

- Perennialism—A “new age” philosophy proposes that many truths can be morally relevant to individual facts and that spiritual experience can happen outside of organized religion (Hartelius, 2017).

- Complementary Therapies—The third wave of western psychology embraces mindfulness and alternative therapies as an integral portion of the healing process (Vazquez & Jensen, 2020).

- Lay Healing Ministry—Unregulated, non-clinical, Christian lay practitioners use various spiritual and healing techniques to heal people outside clinical psychotherapy (Garzon & Tilley, 2009).

- Universal Life Force—A non-religious spiritual biofield that supposedly animates all living beings and can be manipulated and healed via alternative medicine practices (Bidwell, 1999).

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine—An emerging field of non-traditional healing practices such as yoga, chiropractic, acupuncture, meditation, and homeopathy (Brown, 2013).

Summary

In conclusion, this research design was built upon the existing conversation regarding developmental trauma, C-PTSD, family systems theory, attachment dysfunction, and betrayal trauma. This focus likewise lifted the argument out of the medical model’s authority and into the hands of the researchers. It appears that the medical world of allopathic mental-health care has historically moderated non-clinical voices in the conversation as invalid. This dynamic has been to protect the patient in a similar way that evangelical pastors have attempted to protect the flock. Unfortunately, this has left the issues in the hands of authoritative theologians and doctors who do not often enjoy having their authority questioned. Those who dissent from these professional opinions face real repercussions. Furthermore, this model has created a large void between ministry and medicine. CTs seems to exist between the two. Meta-synthesis would deconstruct the appeal to authority in the theological and medical arenas. Although experts’ opinions were weighed, the results were no longer based on this illogical fallacy regarding authority.

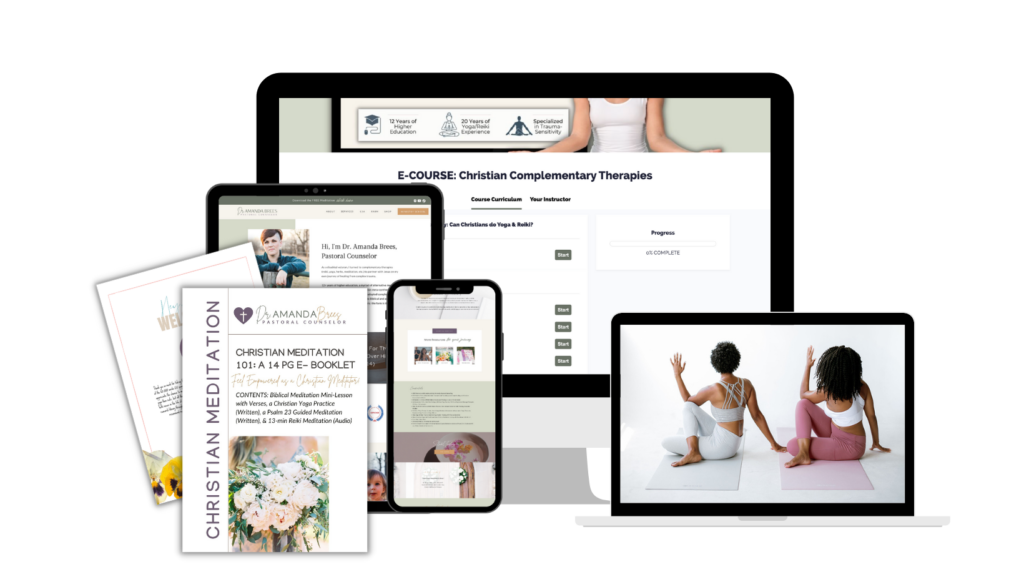

Do you want to learn more?

Are you interested in learning more about Christian complementary therapies? Check out the e-course for more information!

References

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment