Pentecostal Faith Healing and Complementary Therapies. Brown (2014) has been following the charismatic and Pentecostal revivals sweeping North America for more than 10 years. During this time, she has noted an overlap between CTs and charismatics. Often, these conservative believers get disillusioned with modern medicine. Brown noted that Pentecostals tend to view spiritual healing in a more complementary way. Previously, all Eastern, new age and complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) practices were rejected as idolatrous. Today, many Christians are falling for the idea that CAM can be spiritual but not religious, and therefore aid in Christian devotion. She noted the existence of a universal life force that permeates most CAM practices, including chiropractic, acupuncture, homeopathy, yoga, Reiki, meditation, and martial arts. Brown (2014) asserted that adherents often believe that the activity of the Holy Spirit found in charismatic outpourings is comparable to sensations experienced during a Reiki session. This dynamic leads adherents to attribute the Holy Spirit to both movements. Prayer for healing often focuses on touch, and the healing comes through the Holy Spirit in Jesus’ name instead of manipulating the human energy field through impersonal spiritual energy (Brown, 2014).

Christian Adaptability. Pastors, lay ministers, and parachurch ministries traditionally offer counseling and healing services to the hurting and broken. Under the scope of practice laws, ministers have legal protections to help to hurt individuals, couples, and families in ministry outside of clinical mental health counseling (Stone, 1990). Therefore, these ministers and modalities of inner healing and deliverance prayer minis fall into complementary therapies’ legal context. So, on the one hand, pastoral counselors and lay ministers can legally offer essential services. On the other hand, they are faced with this influx of eastern healing practices that are increasingly taking root in the context of healing individuals and families. Certain conservative evangelical Christian-thought leaders advocate for the Christian adaptability of these mindfulness offerings in the context of lay ministry (Garzon & Ford, 2016). In the same way, Christians adapt practices like Christmas. These authors contend for CTs to be used by Christians with specific parameters. Other conservative evangelical Christian thought leaders vehemently oppose the use of CTs by Christians (Brown, 2018).

Positions of Christian Complementary Therapies

Christians Should Not Practice CAM. Brown (2014) noted that there is no Protestant equivalent to the formal Catholic warning about the dangers of CAM for Christians. Nevertheless, religion and spirituality share common assumptions and should not be used by Christians to avoid the reality of practicing non-Christian modalities. Brown, therefore, defines spirituality as another religion. She also noted the American historical phenomenon of disillusionment with the medical and religious community that birthed both the charismatic-renewal and holistic-health movements unhappy with pastors and doctors. She disagrees with the ability to Christian-adapt CAM due to the scientific efficacy. She disagrees with the container-contents idea that presents CAM as a neutral container filled with Christian or non-Christian content. She disagrees that one’s intent can impact the suitability of such practices for Christians (Brown, 2014).

CAM Is Not Religious. Jain (2012) provided an in-depth history regarding the roots of these concerns. She explained the pre-colonial roots of yoga as a system of consciousness-refinement through meditation and mastery of the mind-body connection. This system pre-dated Hinduism. The introduction of physical postures came into existence recently. These postures were intended to help practitioners prepare to sit in extended meditation. Hindus make unfounded claims that yoga belongs to their religion. Evangelical pastors such as Mark Driscoll, John MacArthur, and Pat Robinson openly highlight this connection to Hinduism. Most forms of modern yoga claim to fit within the context of any religion. Anusara yoga is a brand that claims to have religious roots in tantra. Holy yoga is a form of Christian yoga not rooted in any religion. Instead, it helps strengthen the practitioner’s connection to Christ outside of the realm of religion. In summary, the system itself lies outside the context of any world religion (Jain, 2012).

Postural yoga is a means to the end goal of meditation, and meditation appears to be at the root of the controversy of Christian appropriateness. Meditation was mentioned in Psalm 104:34, “May my meditation be pleasing to him” (New International Version). Although that is a far cry from a full biblical doctrinal statement, it is nevertheless listed as a clear biblical concept. One could argue it is even mandated. Still, that fails to adequately deal with the myriad of cultural and religious overtones that have been placed upon most complementary therapies. Practices such as Reiki, meditation, and yoga appear to be effective in treating trauma, but do the benefits outweigh the theological risk for evangelicals? Is the mystical non-religious element of meditation questionable due to the ambiguity of the practice? Or is it acceptable for Christians to adopt the practices with specific Christian accommodations?

CAM is Apostasy. Brown (2013, 2015) is one researcher attempting to have the hard conversations regarding Christian opposition to CTs. She takes this a step further when she discussed the phenomenon of CTs and Pentecostal healing. Brown noted Bethel Church in Redding, California, in her quest to obtain medical documentation for the healings coming from one of the largest charismatic churches with a global reach. She stated that CTs, including Reiki, have done a much better job attempting to validate their findings empirically. Furthermore, Christian prayer has more empirical support than CTs, but CTs are gaining much quicker acceptance into the biomedicine world due to their willingness to abide by the codes of the scientific method. Brown cited the incident of Heidi Baker’s claims to have been healed of a deadly case of MRSA by Jesus. Indeed, the results of her medical records validated the claims by providing additional information to outsiders. Brown (2013, 2015) cited Christian spiritual healing (CSH) as a term used to describe these non-CT-based spiritual healing phenomena prevalent in today’s charismatic and Pentecostal worlds, and research identified this term, CSH, for the emerging overlap between CTs and lay-Christian healing ministry.

Yoga Is Devotional. Some assert that yoga is simply a tool like fasting. It can therefore be adopted by any religion and used to promote spirituality. Others agree with the notion that yoga is decidedly Hindu. Neumann (2019) described Yoganada’s theology in depth. First, Yogananda asserts that the purpose of meditation is a pathway to the divine and knowing God. His kriya yoga (KY) system aims at attaining a direct, personal experience of God. Yogananda was notorious for his indifference toward postural yoga. He aligned with the bhakti tradition of devotional yoga. He considers yoga to be the science of religion. His teacher was Sri Yuktesawar, who taught an esoteric variation on modern yoga. The goal is to be liberated and escape the illusions of this lifetime (Neumann, 2019). Yoga poses itself as a science because it seeks to obtain a particular way of knowing God through direct experience. It seems that Sri Yukteswar used the language of modern evangelicalism without adopting its theology of it to explain Hindu lore. The goal is also to destroy attachments to this world and overcome samskara. KY attempted to use the ministry of yoga as a means of God-realization. Nevertheless, KY found a home in Southern California among a wave of Pentecostal healing practices and new thought. This season was a time in human history when yoga was lumped into a category of suspicion with astrology and hypnotism (Neumann, 2019).

American Yogic Roots and Philosophy

Neumann (2019) further described a phenomenon where health-seekers were often mixed spirituality into their health practices. When Yogananda lived in Los Angeles, it was home to a mixture of faith healers, healers, Astro-therapists, and unorthodox medical practitioners, all tinged with spirituality. Ironically, Yogananda seemed to mirror Aimee Semper McPherson’s movement of healing through Christ’s power. He seemed to be modeling his movement after Pentecostal evangelical revival pastors. In some ways, he was capitalizing on divine yoga by using distance education to enroll followers into the fellowship. In yogic philosophy, reality consists of five koshas, or sheaths, essential stages of evolution that all matter passed through to become free (Neumann, 2019). Creation is a delusion, and human experiences are based on endless cycles of reincarnation that result from karma, or the law of cause and effect. KY included elements of tantra yoga and kundalini. At the core, KY promoted the goal that the devotee, meditation, and God become one. Therefore, yogic philosophy aims to surrender to God through a deep, emotional relationship with God. Furthermore, the goal is to release from cycles of birth and death. KY is an essential counterpoint to the dominant narrative that yoga was safely secularized in modern yoga (Neumann, 2019).

Religious Borrowing and Appropriation. Some practitioners claim it is indeed possible to practice multiple spiritual identities. Bidwell (2015) described makes claims to the religious multiplicity of a Buddhist-Christian. He noted that his Buddhist identity lends itself to a works-based tendency, whereas his Christian identity lends itself to grace, radical love, and intimacy. Unity in diversity is a claim Bidwell adheres to as a vipassana practitioner and Presbyterian minister. He asserted that Christian spiritualists are at the forefront of a movement that allows the practice of the spiritual self in an interreligious world (Bidwell, 2015). Zwissler (2011) explained that Christians have long been adopting practices such as Christmas and Easter. Some go so far as to label this long-held process appropriation based on White privilege and sometimes xenophobia. She asserted that Christian borrowing practices have often attempted to scapegoat paganism. This issue is all happening as conservative North American evangelicals attempt to build a new orthodox Christianity plagued with explicitly anti-feminist rhetoric (Zwissler, 2011). Bidwell (2015) made a salient point regarding this complex dance of addressing public issues for the benefit of many without falling into the tendency to perpetuate White and Christian privilege or minimize other religions’ impact.

Ellison et al. (2012) found that people who identify themselves as spiritual or religious are more likely to use religious forms of CAM like prayer, meditation, and spiritual healing. Spiritual non-religious people were found to use mind-body therapies instead. Zeugin (2017) noted that CAM had become part of Switzerland’s medical field. She critiques Brown’s limitations in assessing the CAM field through written accounts. Instead, she proposes that we should not categorize entire medical and religious systems as a single unit. There is often a complicated intersection of medicine and religion that must be adequately accounted for when deciding whether CAM is entirely religious (Zeugin, 2017). Pedersen et al. (2013) advocated for clarity between this complicated distinction between faith and God and faith in a higher power.

Klassen (2005) described a baptized Christian who was turned away from being initiated into enlightenment by ordination as a Buddhist monk because he was a Christian. This man, who is now a Christian pastor, explained that the theology of energy is universally accessible whether people are aware of it. Translation into Christian terms is not misappropriation or heresy. It is an embrace of an evolving Christian spirituality. This dynamic is in stark contrast to those who oppose CAM. These hostile reactions to inter-religious energies are based on inadequate understanding and xenophobic historicizing. They are unusually suspect of all non-Western attempts at wisdom in a biomedically dominant society. This phenomenon is rooted in a religious past of Christianity that idealizes missionary triumphalism and pathologizes religious others (Klassen, 2005). These liberal Christians suggest that CAM practices can transform the new evolution of Christian contemplation and healing practices. They encouraged Christians to include crosses instead of Hindu deities, practice in a church, or use a Christian sacrament of laying on their hands or using a Christian prayer instead of a Hindu mantra. They encourage the Christian adaptability of CAM. These Christians hope to move beyond the White, Western, Christian limitations of their worldview while still holding onto the meaningfulness of this identity (Klassen, 2005).

Research Gap

This study would also help further amplify familial trauma as the primary goal of ministry. This study would build upon somewhat older family systems and attachment trauma theory in the research. It would also help clarify this specific subset of C-PTSD that seems to appear as multiple psychiatric diagnoses at times. Hopefully, identifying this specific type of trauma will expedite and streamline both lay and clinical attempts to heal complex trauma rooted in family systems. Clinicians, practitioners, clients, congregants, and ministers could all benefit from greater insight into the theory of Christian-adaptable CTs for familial trauma. The synthesis would help connected seemingly unrelated topics. Hopefully, this would also help reduce the somewhat overwhelming amount of training needed to help survivors of familial trauma effectively. This process could be done by identifying the roots of their symptoms alongside the most effective treatment options. CTs are now emerging as a vital missing piece of this equation. Finally, integrating the issue of the ministry component would better help distribute these healing resources outside the world of mental health. Pastoral counselors have ready access to couples, families, and individuals in need of healing. They also offer needed oversight regarding how to pastor evangelicals through the proper use of such modalities for Christians.

Conclusion

Familial trauma is a subset of C-PTSD. It is a type of relational trauma that exists in family systems with roots in attachment theory. Betrayal trauma is a component of family trauma that involves the unhealthy dynamics of families who struggle with traumas such as substance abuse, mental illness, and enmeshment. Complex trauma presents a unique set of symptoms unique from acute trauma. These symptoms respond best to an integrative approach to healing which involves a top-down and bottom-up approach. Top-down approaches include modalities like talk therapy. Bottom-up approaches include modalities like yoga therapy. The goal is to regulate the unbalanced nervous system and address the parts of the brain that have developed maladaptive responses to relational chaos. Pastoral counselors are uniquely equipped to help pastors and counselors address the issue of Christian adaptability for healing complex trauma rooted in attachment dynamics.

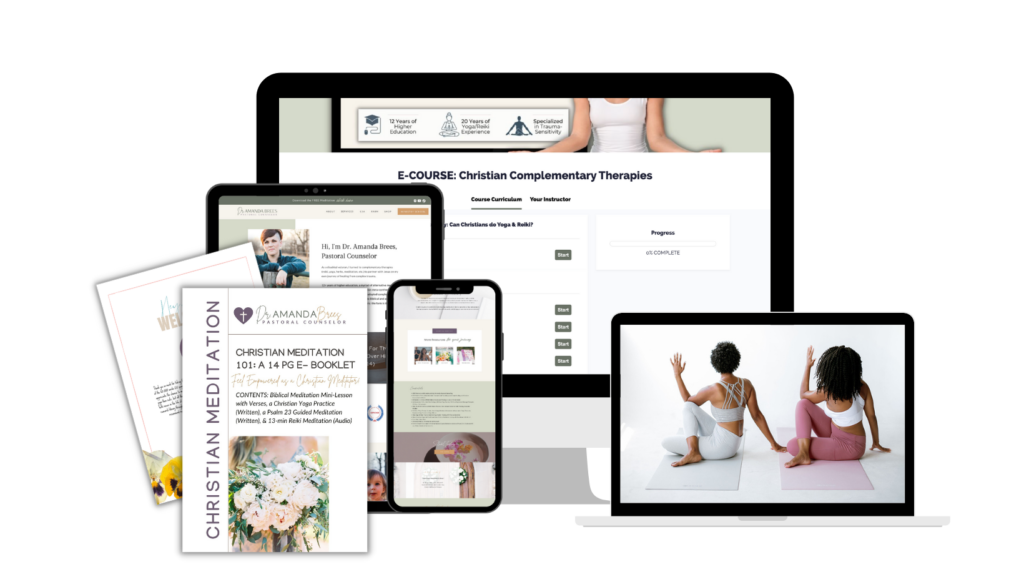

Want to learn more about yoga therapy for Christians?

Take the e-course!

References

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment