A phenomenon of the new age movement is a renewed interest in shamanic and indigenous healing practices. Faith healers and the Tree of life are also the subjects of much new age interest. Wise men and prophets rely on spiritual insights and power similar to shamans and medicine men. Jesus’ life is marked by operation in these supernatural insights and healings. Like today, these mystical and healing acts upset the pharisaical and religious leaders, “The Pharisees were left sputtering, “Hocus-pocus. It’s nothing but hocus-pocus. He’s probably made a pact with the Devil” (Matthew 9:34). This is a common accusation of evangelicals against all forms of non-traditional spiritual and mystical practices in the new age and Pentecostalism.

Like a shaman, Jesus casts demons out of the madmen in Mark 5. Jesus was also accused of practicing black magic when operating in the supernatural: “Jesus delivered a man from a demon . . . But some from the crowd were cynical. ‘Black magic,’ they said. ‘Some devil trick he’s pulled from his sleeve.’ Others were skeptical” (Luke 11:14-16). Jesus admonished this religious Spirit when he said, “You have your heads in your Bibles constantly because you think you’ll find eternal life there. But you miss the forest for the trees. These Scriptures are all about me” (John 5:39-40). In John 8, Jesus said, “‘I am who I am long before Abraham was anything.’ That did it—pushed them over the edge. They picked up rocks to throw at him. But Jesus slipped away, getting out of the temple” (John 8:48-59). Jesus was capable of readings minds when he was once more accused of using black magic:

Jesus knew what they were thinking and said, “Any country in civil war for very long is wasted. A constantly squabbling family falls to pieces. If Satan cancels Satan, is there any Satan left? You accuse me of ganging up with the Devil, the prince of demons, to cast out demons, but if you’re slinging devil mud at me, calling me a devil who kicks out devils, doesn’t the same mud stick to your own exorcists? But if it’s God’s finger I’m pointing that sends the demons on their way, then God’s kingdom is here for sure.”

(Luke 11:17-20)

That same pharisaical Spirit present in today’s fundamentalist yogaphobic and anti-CAM culture had him turned over to the Romans for crucifixion (Matthew 27). It is essential to uphold sound biblical doctrine and avoid judging this religious Spirit. That said, Jesus was straightforward with this group, and the Church has a long history of crusades, witch hunts, and inquisitions. Christians must remain vigilant in avoiding religious multiplicity and moral pluralism. However, it is also crucial for the Church to find more productive ways to manage theological disagreements about the Spirit’s CAM and gifts. An example that comes to mind is the fundamentalist accusations that the Pentecostal movement uses black magic to produce modern-day miracles and healings. This same Spirit often disapproves of all CAM due to its spiritual origins.

This supernatural power continued with the disciples, “Right and left they sent demons packing, they brought wellness to the sick, anointing their bodies, healing their spirits.” In Acts 8, Paul laid hands on a man, and he was healed. In Acts 16, a psychic fortune teller followed Paul around, telling everyone he was working for the most-high God and laying out the road to salvation. Eventually, Paul cast the Spirit out of her when she would not stop. Ironically, he was operating in similar power as she was. What appears different was from her was his source of healing and intention. Operating in the supernatural was outside his pharisaical background but ordinary in his ministry after his supernatural conversion experience on the road to Damascus (Acts 9:3-5). Stephen, who would eventually end up martyred, practiced the unmistakable signs and mystical workings (Acts 6).

Astrology, Solstices, and New Moons

Astrology, new moon, and solstice celebrations are suspect in evangelical circles for understandable reasons. However, they are another common topic of interest in the new age movement. Jung et al. (2018) was interested in astrology as a spiritual mechanism for understanding the unconscious. He considered it the summation of the entirety of the psychological knowledge in antiquity (Jung et al., 2018). Astrology is regarded as one of the sister sciences of yoga and Ayurveda. It can be viewed as another prophetic gift often used to listen to God. Although by no means a science, the Bible mentions the spiritual influence of the heavens on the earth in Job 38: 31-33:

Can you catch the eye of the beautiful Pleiades sisters, or distract Orion from his hunt? Can you get Venus to look your way, or get the Great Bear and her cubs to come out and play? Do you know the first thing about the sky’s constellations and how they affect things on earth?

Likewise, the wise men used this study of the stars to locate Jesus after his birth (Matthew 2). Luke 21:25 stated, “There will be signs in the sun, moon, and stars.” The new moon, a central part of astrology, is discussed and sometimes used as a central part of worship: “Also at times of celebration, at the appointed feasts and New Moon festivals, blow the bugles over your Whole-Burnt-Offerings and Peace-Offerings; they will keep your attention on God.

I am your God” (Numbers 10:10).

The Bible seems less concerned with the possibility that the heavens might provide spiritual insights into our lives on earth. Instead, the Bible is abundantly clear that believers cannot adopt the pagan practices of worshiping the sky (Deuteronomy 4, 17, 2 Kings 21, 2 Kings 23, Jeremiah 8, Isaiah 47). Believers are further warned to rely on God for the final say in direction and guidance about their lives and futures; 2 Kings 21:11-15 stated,

He worshiped the cosmic powers, taking orders from the constellations. He built shrines to the cosmic powers . . . He burned his own son in a sacrificial offering. He practiced black magic and fortunetelling. He held séances and consulted spirits from the underworld.

Crystals, Gemstones, and Precious Stones

Crystals are a common phenomenon in spiritual and new-age tourism destinations. Evangelicals often assume spiritual seekers are worshipping crystals, but often these are simply another spiritual tool created by God and therefore adaptable. Furthermore, they are mentioned in the Bible and used in worship: In Exodus 25, the Ephod is set with various crystals, anointing oil is used in worship, and incense is ritually used in worship. “Now make a(n) . . . Ephod . . . Mount four rows of precious gemstones on it. First row: carnelian, topaz, emerald. Second row: ruby, sapphire, crystal. Third row: jacinth, agate, amethyst. Fourth row: beryl, onyx, jasper. “Set them in gold filigree. The twelve stones correspond to the names of the Israelites” (Exodus 28: 15-20). In Ezekiel 28:14-16, it says, “You were in Eden, God’s garden. You were dressed in splendor, your robe studded with jewels: Carnelian, peridot, moonstone, beryl, onyx, and jasper, sapphire, turquoise, and emerald, all in settings of engraved gold.”

Incense, Herbalism, and Anointing Oil

The use of incense in spiritual practices is a typical new age practice. Likewise, the inclusion of various phytotherapy remedies and their more subtle derivatives is another shared interest of the new age. Naturopathy, homeopathy, and herbalism have experienced a CAM resurgence due to their spiritual and natural roots. Some of these modalities use biomedical approaches to health, while others rely on extraction and manipulation of the subtle energy field to promote healing. There are 146 references to incense, herbs, and essential oils in the Bible. In Exodus 30, 1 Chronicles 29, 2 Chronicles 16, and Ezra 6, anointing and oil and incense are used as integral parts of worship.

In 1 Chronicles 3, 2 Chronicles 9, 2 Chronicles 32, Ezekiel 1, Isaiah 54, Revelation 22, and Revelation 4, crystals are mentioned as integral parts of worship or spiritual experiences surrounding the throne of God. The Bible makes further mention of crystals, “The leaders brought onyx and other precious stones for setting in the Ephod and the Breast piece. They also brought spices and olive oil for lamp oil, anointing oil, and incense” (Exodus 35:27). “On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh” (Matthew 2:11).

Meditation and Mindfulness

CTs encompass a myriad of mindfulness practices, such as postural yoga with roots and intentions focused on meditation. Although the Bible does not speak to the modern phenomenon of postural yoga, it does speak to its end goal and roots of meditation. It appears that the practice of meditation itself is entirely biblical. Notable verses on meditation include the following: “Be still and know that I am God.” (Psalm 46:10), “May my meditation be pleasing to him, as I rejoice in the LORD” (Psalm 104:34, New International Version), “I will meditate on your precepts and fix my eyes on your ways” (Psalm 119:15, English Standard Version), “I will consider all your works and meditate on all your mighty deeds” (Psalm 77:12, NIV), “And Isaac went out to meditate in the field toward evening” (Genesis 24:63, ESV), “God deals out joy in the present, the now” (Ecclesiastes 5:20, MSG), Isaiah 43:19, “Be alert, be present,” and Matthew 6:6, “Find a quiet, secluded place so you won’t be tempted to role-play before God. Just be there as simply and honestly as you can manage. The focus will shift from you to God, and you will begin to sense his grace.”

Other biblical perspectives on meditation include 1 Corinthians 14:13-17: “I should be spiritually free and expressive as I pray, but I should also be thoughtful and mindful as I pray. Mary and Martha are examples of contrasting the practices of being with Jesus versus doing” (Luke 10).

Laying on of Hands, Healing Touch, and Reiki

Reiki is a Japanese word that describes an Eastern interpretation of the laying on of hands practices that support spiritual and emotional healing. Healing Touch Spiritual Ministry is a Christian-adapted form of Reiki for Christians. It attempts to manipulate biofields and subtle energy like acupuncture without the needles. It operates on a more subtle realm than indigenous shamanic practices. Meditation is a primary goal of Reiki as well. This CAM modality is often highly suspect in evangelical circles due to the eastern variations of the methods. In Mark 10, Jesus said, “Your faith has saved and healed you.” He healed those who need it (Luke 8). Yet, the practice of Laying on of Hands is also quite biblical and central to Jesus’ ministry:

She was thinking to herself, “If I can put a finger on his robe, I can get well.” The moment she did it, the flow of blood dried up. She could feel the change and knew her plague was over and done with. At the same moment, Jesus felt energy discharging from him. He turned around to the crowd and asked, “Who touched my robe?”

(Matthew 5:29-30)

This Greek word for energy is dunamis (δύναμις). It is used 120 times in the Bible (Strong, 1890). Strong defines it as a “force (literally or figuratively); especially, miraculous power (usually by implication, a miracle itself)” (p. 1411). This force, power, or energy appears to be the same biofield subtle energy at the heart of most CAM practices today. Jesus seemed to operate in the same capacity at his transfiguration in Matthew 17. This force emanates from Jesus in Luke 6:18-20, “Those disturbed by evil spirits were healed. Everyone was trying to touch him—so much energy surging from him, so many people healed!” (Luke 6:18-20).

Furthermore, “God formed Man out of dirt from the ground and blew into his nostrils the breath of life. The Man came alive—a living soul!” (Genesis 2:7). This breath of life appears to be consistent with the subtle life force energy that underlies the basis of most CAM practices. It appears to permeate the flesh, or dirt, man was formed out of and animate the human spirit. Although this is far from a direct correlation to life force, it does seem entirely biblical that humans have a spirit that leaves the body upon physical death. This breath of life, or subtle energy body, is what differentiates a deceased human corpse form an animated living human being. This breath was given to humanity by God as a central portion of the creation narrative.

Table 7 shows pertinent biblical references to New Age and CAM principles.

Christian Adaption

Table 7

New Age Biblical References

Astrology | Crystals | Meditation | Reiki |

| Ezekiel 26:1, 29:17 Haggai 1:1 Genesis 1:14 Psalm 148:1-6 Psalm 147:4-5 Psalm 19 1 Peter 2:4-5 2 Chronicles 2:4 Nehemiah 10:33 Ezekiel 44:24, 45:17 Luke 2:1-12 Leviticus 23:1-2 Leviticus 23:4 Genesis 8:22 Psalm 74:17 Amos 8:5 Nehemiah 10:31 Numbers 10:10, 28:11-15 1 Chronicles 23:31 2 Chronicles 8:13, 31:3 Ezra 3:5, Job 38:31-33Ezekiel 46:1, 3, 6 Colossians 2:16 Acts 18:21; 27:9 1 Corinthians 5:7-8 | Exodus 24:10, 25:7, 28:9, 17, 31:5, 35:9, 35:27, 39:10-13 2 Samuel 12:30 1 Kings 10:2 1 Kings 10:10 1 Kings 10:11 1 Chronicles 20:2 1 Chronicles 29:8 2 Chronicles 3:6 2 Chronicles 9:1 2 Chronicles 9:9 2 Chronicles 9:10 2 Chronicles 32:27 Song of Solomon 5:14 Isaiah 54:12 Ezekiel 27:22 Daniel 11:38 Revelation 18:12 Revelation 18:16 Revelation 21:11, 18-20 | Psalm 19:14 Psalm 49:3 Psalm 104:34 Genesis 24:63 Joshua 1:8 Psalm 1:2 Psalm 39:3 Psalm 48:9 Psalm 77:3 Psalm 77:6 Psalm 77:12 Psalm 119:15 Psalm 119:23 Psalm 119:27 Psalm 119:48 Psalm 119:78 Psalm 119:97 Psalm 119:99 Psalm 119:148 Psalm 143:5 Psalm 145:5 | John 14-12 Luke 4:40 Matthew 8:14-15 Mark 1:40-42 Luke 5:12-13 Matthew 20:29-34 Mark 6 Mark 8:22-25 Mark 7:32 35 Luke 7:12-15 Luke 8:49-55 Luke 9:1-2 Mark 6:5-6 Matthew 13:10-11 Mark 4:10-12 & 34 |

Complementary therapies should not be wholesale accepted as already Christian appropriate due to the Hindu and Buddhist-adapted versions of the practices present in CAM. However, they should also not be wholesale rejected given the merit of the mechanism of action and the tools to be Christian-adapted. Instead, many of these practices can be redeemed, and many are even biblical. Yet, discernment is mandated for all Christians. A Christian-adapted, biblical perspective of these practices accepts that these practices and tools are spiritually neutral by their merit of being created by God, and therefore redeemable. Christians must prayerfully pray and seek wise counsel regarding what needs adapting and how. It would behoove them to consider the advice of 2 Kings 21:1-6:

He worshipped the cosmic powers, taking orders from the constellations . . . And he built shrines to the cosmic powers and placed them in both courtyards of the Temple of God. He burned his own son in a sacrificial offering. He practiced black magic and fortunetelling. He held seances and consulted spirits from the underworld.

Colossians 2:6-8 admonished, “You don’t need a telescope, a microscope, or a horoscope to realize the fullness of Christ and the emptiness of life without him.” It could be possible for Christians to adapt spiritual practices like astrology by only taking orders from and worshiping God even if they choose to celebrate monthly New Moons. Note, astrology is not included in this list of expressly prohibited practices. Although Christians are quick to consider it fortune-telling, the prophets could be likewise considered fortune-tellers. Christians might instead prayerfully consult the Holy Spirit about one’s future and listen carefully to the Holy Spirit about making sure they are receiving proclamations about their fate and destiny only from God.

Astrology itself is more interested in aiding adherents in cultivating self-realization as a sister science of meditation than dooming a person to a dark fate outside of God’s will and plan for a person’s life. Jeremiah 29:11 stated, “I know what I’m doing. I have it all planned out—plans to take care of you, not abandon you, plans to give you the future you hope for.” A horoscope simply shares the spiritual weather in a similar way a weather forecast predicts the future. Preparing oneself for inclement spiritual weather could leave room for Christian debate and openness to listening to the Holy Spirit. Dooming a person to a hellish fate through fortune-telling is strictly prohibited.

This process is an example of what and how to adapt a CAM practice. Paul stated, “God decides on the outsiders, but we need to decide when our brothers and sisters are out of line and, if necessary, clean house” (1 Corinthians 5:12). The Christian community would be an ideal place to have hard conversations regarding what and how to adapt these practices in light of scripture and the Holy Spirit’s guidance. It would behoove Christians to support one another in increasing the discernment of what and how to adapt CAM without wholesale accepting or rejecting it and then placing their convictions on others.

In summary, these tools are neither inherently Christian nor non-Christian in the same way money and sex are neither Christian nor non-Christian. Christians might utilize these tools, but they can be misused. It is therefore vital that Christians seek wise counsel, pray, consult Scripture, and stay in the Christian community regarding what and how to adapt neutral spiritual tools such as meditation. Although the practice might absolutely be adaptable, the discerning Christian should understand that the version of CAM they are encountering may need adapting. Furthermore, pastoral counselors should be on the lookout for opportunities to educate congregants regarding how to better adapt spiritual tools with Christian integrity.

Delimitations and Limitations

Limitations

The primary weakness of this study is the inability for a single, novice researcher to adequately survey enough data. Meta-synthesis traditionally requires a research team that can help survey much more data. It also helps overcome researcher bias. In this case, the greatest limitation is that the nature of metasynthesis relies heavily on the researcher knowing what they are looking for. In this case, the researcher brought the following experience and bias to the research. That said, this bias presents an incredibly unique lens which might also be the research’s greatest novel contribution as well. The bias is narrated as an N = 1 case study, but no actual case study was conducted.

Case Study Narrative

The researcher is a 33-year-old female from a small farm in the Midwest. She was raised in a Lutheran home with conservative Christian values. She gave her life to Jesus at an evangelical Bible camp at age 9, and read her entire Bible by age 10. She attended a fundamentalist church alongside her Lutheran church thereafter. She was confirmed Lutheran in eighth grade and joined the worship and leadership teams of her youth group. Around age 15, she began struggling with symptoms of developmental trauma. At age 17, she experienced a traumatic event at her evangelical church which precipitated her attending a marriage and family therapy with a Christian psychologist. During this time, she brought her family of origin with her to therapy for treatment. To cope with her symptoms, she turned to CAM modalities. These modalities proved vital to managing her worsening symptoms of developmental trauma. Given the questionable nature of CAM, she was required to meet with both her Lutheran and Evangelical Free pastors to justify her choices.

After this, she joined the United States Army National Guard to work as a Chaplain’s Assistant in order to escape the negativity. During her time in active duty, she experienced ongoing revictimization and assault which later resulted in an extreme exacerbation of her symptoms which became unmanageable. She struggled with chronic relationship chaos, anxious attachment issues, and divorce. Her symptoms interfered with her work and education, but she persevered in school. In 2011, she moved to Redding, California, to attend Bethel’s School of Supernatural Ministry. Shortly thereafter, she discovered the internationally known spiritual mecca of Mount Shasta, California, about one hour north of Redding. New age seekers from around the world flock to the community to frequent the myriad of crystal shops, health food stores, and alleged supernatural experiences.

Over the next 10 years, the student author embarked on a journey of reconciling her faith with her new age spiritual practices. She went on to take classes and obtain alternative medicine certificates in yoga teaching, reflexology, Reiki, Healing Touch Spiritual Ministry, astrology, massage therapy, yoga therapy, and Hawaiian shamanism. She also obtained two regionally accredited academic degrees. The first degree was an undergraduate Biblical Studies and Theology degree from the University of Northwestern, Saint Paul, MN. The second was a graduate Transpersonal Psychology degree from the Institute of Transpersonal Psychology (now called Sofia University) in Palo Alto, CA. She wrote her capstone papers for both degrees on the Christian-adapted CAM topics contained in her doctoral dissertation on Christian-adapted CTs for ministering to adult survivors of familial trauma. She was ordained by an independent Christian organization in 2017. She has served as an intermittent volunteer staff member at an Assemblies of God Church in Mount Shasta, CA, since that time, and currently works and resides there. Her small healing ministry was launched in 2013 as a small yoga and Reiki practice. It has since evolved into a Christian-adapted CT practice with a heart of outreach to the new age community of Mount Shasta, CA.

Delimitations

The study was limited to N = 500 research articles for inclusion for practical purposes. The study was also limited to N = 35 articles for the meta synthesis for practical purposes as well. Another delimitation was the analysis of the data. Given the quantity of data and the nature of meta-synthesis, a myriad of possibilities for data synthesis exists. For the purpose of this study, the third-order information that emerged was focused on as a starting point for the conversation. Given the limitation of a single, novice researcher, the study is limited. Yet, this delimitation was overcome in part given the length of this study was a doctoral dissertation. Considerable time and energy were able to be poured into the qualitative synthesis portion through the use of Atlas.ti software.

Recommendations for Future Research

Furthermore, it would be advisable for a large team of researchers to embark on their own journey of metasynthesis pertinent to the topics at hand in this study. Ideally, more quantitative data is needed especially in validating Christian sensitive and adapted methods for healing trauma. Additional research is needed on what and how to adopt CTs for Christian use. It could be advisable for other researchers to analyze the Atlas.ti results and findings in this study to come to their own conclusions about the data set. Most importantly, the dissemination of what and how to adapt CTs for use in ministry settings is paramount. Ideally, more focus needs to be placed on how to effectively oversee and manage the training of lay ministers. Although there is a great need for empirically validating Christian fourth-wave trauma treatments, there is an equal need to assist in more streamlined processes of training for those who are not clinicians. The results of the findings greatly impact lay ministers, pastoral counselors, and counselors needing practical answers for healing individuals and families. The following section describes a possible draft outline for how to evolve the process of leveraging evolving research on these topics to the end of assisting growing ministries.

Contemplative Christian Healer (CCH) Practitioner and Teacher School of Ministry

It would be advisable for researchers to spearhead and oversee a research team that informs a continuing education certification course for CCT providers in partnership with an organization like CCHA. This organization would be a non-clinical organization with a general overlap with CCBT. This organization would focus on streamlining the training and certification of CCHs. It would train practitioners and teachers who could offer CCH in their communities. In addition, it would provide various levels of accreditation for Christian Contemplative Healers (CCHs) of all kinds.

Introductory Training

This level of training might include an introductory 50-hour, on-demand, online training course that teaches the basics of the contents of Christian-adapted CTs for familial trauma. This course would seek to streamline the currently arduous process of learning the basics of Christian CTs for implementation into the various clinical, practitioner, educational, and ministry settings. For example, a Christian yoga teacher might take this introductory course to learn how to successfully Christian-adapt their classes. It might also provide evangelical CT practitioners, and teachers needed for community and direction. A Christian pastor might take this course to learn how to address the issue of CTs from a decidedly Christian standpoint.

Intermediatory Training

The second course might be a 200-hour certification similar to Yoga Alliance’s standard 200-hour yoga teacher training. This certification could provide a solid foundation for researchers, teachers, pastors, counselors, ministers, and practitioners of all sorts to integrate contemplative Christian CTs into their existing offerings and specialties. This process could parallel how a clinician might train in DBT even though their graduate degree is in Marriage and Family Therapy.

Advanced Training

The third level of training might mirror the structure of lay-ministry training and Bethel’s School of Supernatural Ministry or the International House of Prayer’s Forerunner School of Ministry. This program could be a year-long practitioner training with different specialties such as worship, creative arts, and meditation. The curriculum could potentially attempt to work with Yoga Alliance to offer continuing education credits for a Christian meditation teacher (CMT) program. Ideally, candidates for that program would have already completed a Yoga Alliance approved 200-hour teacher training program.

Department of Education Accredited Certifications

Finally, a graduate certificate program and AA program through an accredited university such as Liberty might be a long-term goal to suitable means distribute these teachings to those who want to become a teacher of the method. This program could be offered at the associate’s level as a certificate program (500 Hours) for healers, CT practitioners, and lay counselors. The program could be provided at the graduate level as a certificate program for clinicians, pastors, and professors. The curriculum could include a myriad of training such as Christian yoga, meditation, and laying on hands in conjunction with the what and how’s that need adapting in secular and common CT modalities in the culture currently.

Although the specifics for such a concept remain malleable, the need remains evident. Evangelicals are being faced with a need for their voice to be heard in an ever-changing spiritual climate. Although a Catholic meditation organization exists, there is a clear need for an evangelical protestant organization focusing on healing ministry to emerge. Furthermore, the organization of a formal method would allow Christians the opportunity to stay relevant in this ever-changing world of Christian spirituality and healing. Although these steps are ambitious, they are possible.

The following diagram (Figure 9) presents the reader with a flowchart of the overview of the findings.

Figure 9

Flowchart of Findings Overview

Summary

I contend that meditation represents the essence of the mechanism of action on trial in American evangelical Christian culture:

- It has been established that the benefits of practicing meditation are superior to not practicing for both health and spiritual reasons of union with God.

- Appropriation implies misuse of a culture’s tradition and intellectual property theft, but meditation is the property of no religion.

- Yet, because it is a tool for spirituality used by all religions, it makes sense that evangelicals must guard against Hindu and Buddhist adaptions of meditation present in American culture today. This concept aligns with Brown’s (2018) admonitions.

- Yet, Brown (2018) and Knabb et al. (2021) advocated for the release of Christian-adapted mindfulness and yoga and instead contend for Christian sensitive practices.

Therefore, I contend that Christian-adapted CTs:

- Can be adapted because they are essentially public domain tools (Jain, 2012).

- Need to be adapted to a Christian worldview instead of accepted wholesale

(Brown, 2018). - Are consistent with the third and fourth waves of behavioral therapies’ integration of meditation and CTs treatment of complex and familial trauma (Knabb et al., 2021).

- Are potentially superior in treating familial trauma than psychotherapy or pharmacology as standalone treatments.

- Beneficial to evangelical Christian’s walk with God instead of treating those who partake as second-class spiritual citizens.

Furthermore:

- Christian meditation and Christian yoga are different than Christian Hinduism or Christian-Buddhism/mindfulness (oxymorons) as they have other intentions that point a tool to Christ (such as Christmas).

- Christians have many choices for their health in American culture like whether or not to attend a yoga class or whether or not to attend Church (Jain, 2012).

- Therefore, it would be wise to continue to identify which mechanisms of action are empirically effective in treating familial trauma and thereby continue clarifying the nuances of what needs adapting and how without policing other evangelicals.

Conclusion

An exciting point Paul made was, “The law always ends up being used as a Band-Aid on sin instead of a deep healing of it” (Romans 8:4). Luke 9:24 stated, “Self-help is no help at all. Self-sacrifice is the way, my way, to finding yourself, your true self.” The new age has an abundance of interest in finding this true self through some of the aforementioned spiritual practices. However, it fails to focus on grace, self-sacrifice, and true healing only found in Jesus. Practices that claim the self to be God, or encourage adherents to worship the self, must be rejected by discerning Christians: “He made to be their true selves, their child-of-God selves” John 1:12. This verse represents a distinction used to determine the ability of spiritual practice to be redeemable.

As Christians, one needs to be diligent to avoid using the commands of the law listed in the Old Testament to police the convictions of fellow believers about CAM. The underlying issue is the heart. Furthermore, believers must allow the iron to sharpen iron regarding these subtleties and nuances according to Proverbs 27:17. An evolved ability to accept the realities of a new age of Christian spirituality with discernment and spiritual maturity will allow pastoral counselors to become more extraordinary thought leaders in engaging the third and fourth waves of behavioral therapy in the spiritual and healing potential of Christian-adapted complementary therapies for healing family trauma.

REFERENCES

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bowlby, J. (1991). An ethological approach to personality development. The American Psychologist, 46(4), 333-341.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.333

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Baldwin, P. R., Velasquez, K., Koenig, H. G., Salas, R., & Boelens, P. A. (2016). Neural correlates of healing prayers, depression, and traumatic memories: A preliminary study. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 27, 123-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2016.07.002

Becker-Weidman, A., & Hughes, D. (2008). Dyadic developmental psychotherapy: An evidence-based treatment for children with complex trauma and disorders of attachment. Child & Family Social Work, 13(3), 329-337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00557.x

Belmontes, K. C. (2018). When family gets in the way of recovery: Motivational interviewing with families. The Family Journal, 26(1), 99-104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480717753013

Berkley, M., & Straus, J. S. (2002). Family therapy and complementary and alternative medicine: The next step in collaborative family healthcare. Families Systems & Health, 20(3), 321-327. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0089587

Bidwell, D. R. (1999). Ken Wilber’s transpersonal psychology: An introduction and preliminary critique. Pastoral Psychology, 48(2), 81-90. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022021209375

Bidwell, D. R. (2000). Carl Jung’s memories, dreams, reflections: A critique informed by postmodernism. Pastoral Psychology, 49(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004617430886

Bidwell, D. R. (2001). Maturing religious experience and the postmodern self. Pastoral Psychology, 49(4), 277-290. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004867421215

Bidwell, D. R. (2009). The embedded psychology of contemporary spiritual direction.

Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 11(3), 148-171. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349630903080947

Bidwell, D. R. (2015). Religious diversity and public pastoral theology: Is it time for a comparative theological paradigm? Journal of Pastoral Theology, 25(3), 135-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/10649867.2015.1122427

Bingaman, K. A. (2011). The art of contemplative and mindfulness practice: Incorporating the findings of neuroscience into pastoral care and counseling. Pastoral Psychology, 60(3), 477-489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-011-0328-9

Bingaman, K. A. (2013). The promise of neuroplasticity for pastoral care and counseling. Pastoral Psychology, 62(5), 549-560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-013-0513-0

Bingaman, K. A. (2015). When acceptance is the road to growth and healing: Incorporating

the third wave of cognitive therapies into pastoral care and counseling. Pastoral Psychology, 64(5), 567-579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-015-0641-9

Birrell, P. J., & Freyd, J. J. (2006). Betrayal trauma: Relational models of harm and healing. Journal of Trauma Practice, 5(1), 49-63. https://doi.org/10.1300/J189v05n01_04

Blanton, P. G. (2011). The other mindful practice: Centering prayer & psychotherapy. Pastoral Psychology, 60(1), 133-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-010-0292-9

Bowen, M. (1976). Theory in the practice of psychotherapy. In P. J. Guerin (Ed.), Family therapy: Theory and practice (pp. 42-90). Gardner Press.

Boyd, J. E., Lanius, R. A., & McKinnon, M. C. (2018). Mindfulness-based treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of the treatment literature and neurobiological evidence. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience, 43(1), 7-25. https://doi.org/10.1503/jpn.170021

Bradfield, B. C. (2013). The intergenerational transmission of trauma as a disruption of the dialogical self. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 14(4), 390-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2012.742480

Briere, J. N., & Scott, C. (2015). Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment (2nd ed., DSM-5 update). Sage.

Brown, C. G. (2013). The healing gods complementary and alternative medicine in Christian America. Oxford University Press.

Brown, C. G. (2014). Feeling is believing: Pentecostal prayer and complementary and alternative medicine. Spiritus, 14(1), 60-67. https://doi.org/10.1353/scs.2014.0002

Brown, C. G. (2015). Pentecostal healing prayer in an age of evidence-based medicine. Transformation: An International Journal of Holistic Mission Studies,

32(1), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265378814537750

Brown, C. G. (2018). Christian yoga: Something new under the Sun/Son? Church History,

87(3), 659-683. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009640718001555

Brown, C. G. (2019). Theologies of medicine and miracles. Society (New Brunswick),

56(2), 141-146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-019-00341-0

Busuito, A., Huth-Bocks, A., & Puro, E. (2014). Romantic attachment as a moderator of

the association between childhood abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Family Violence, 29(5), 567-577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9611-8

Cabral, P., Meyer, H. B., & Ames, D. (2011). Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis. Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10r01068

Carr, S. M. D., & Hancock, S. (2017). Healing the inner child through portrait therapy: Illness, identity, and childhood trauma. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(1), 8-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2016.1245767

Carter, R. B. (1999). Christian counseling: An emerging specialty. Counseling and Values, 43(3), 189-198. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-007X.1999.tb00142.x

Cartledge, M. J. (2013). Pentecostal healing as an expression of godly love:

An empirical study. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 16(5), 501-522. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.696601

Chanler, A. (2017). Mindfulness meets enmeshment: Disentangling without detaching

with embodied self-empathy as a guide. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 4(2),

145-151. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000130

Charkhandeh, M., Talib, M. A., & Hunt, C. J. (2016). The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy and an alternative medicine approach in reducing symptoms of depression in adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 239, 325-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.044

Church, D., Hawk, C., Brooks, A. J., Toukolehto, O., Wren, M., Dinter, I., & Stein, P. (2013). Psychological trauma symptom improvement in veterans using emotional freedom techniques: A randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 201(2), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31827f6351

Cloitre, M., Stovall-McClough, K. C., Nooner, K., Zorbas, P., Cherry, S., Jackson, C. L., Gan, W., & Petkova, E. (2010). Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(8), 915-924. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081247

Coe, J. L., Davies, P. T., & Sturge-Apple, M. L. (2018). Family cohesion and enmeshment moderate associations between maternal relationship instability and children’s externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(3), 289-298. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000346

Corigliano, S. (2017). Devotion and discipline: Christian yoga and the yoga of

T. Krishnamacharya. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 30(4). https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1656

Courtois, C. A. (2004). Complex trauma, complex reactions: Assessment and treatment. Psychotherapy, 41(4), 412-425. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.412

Davis, T. J., Morris, M., & Drake, M. M. (2016). The moderation effect of mindfulness on the relationship between adult attachment and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 115-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.02.080

Dayringer, R. (2012). The image of God in pastoral counseling. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(1), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9536-y

Delker, B. C., Smith, C. P., Rosenthal, M. N., Bernstein, R. E., & Freyd, J. J. (2018).

When home is where the harm is: Family betrayal and posttraumatic outcomes in

young adulthood. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 27(7), 720-743.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1382639

Doehring, C. (2019). Searching for wholeness amidst traumatic grief: The role of spiritual practices that reveal compassion in embodied, relational, and transcendent ways.

Pastoral Psychology, 68(3), 241-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-018-0858-5

Dorahy, M. J., Corry, M., Shannon, M., Webb, K., McDermott, B., Ryan, M., & Dyer, K. F. (2013). Complex trauma and intimate relationships: The impact of shame, guilt

and dissociation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1), 72-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.010

Doucet, M., & Rovers, M. (2010). Generational trauma, attachment, and spiritual/religious interventions. Journal of Loss & Trauma, 15(2), 93-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903373078

Earley, L., & Cushway, D. (2002). The parentified child. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104502007002005

Ellison, C. G., Bradshaw, M., & Roberts, C. A. (2012). Spiritual and religious identities

predict the use of complementary and alternative medicine among U.S. adults.

Preventive Medicine, 54(1), 9-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.08.029

Eng, W., Heimberg, R. G., Hart, T. A., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2001). Attachment in individuals with social anxiety disorder: The relationship among adult attachment styles, social anxiety, and depression. Emotion, 1(4), 365.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.398

Fay, D., & Germer, C. K. (2017). Attachment-based yoga & meditation for trauma recovery: Simple, safe, and effective practices for therapy. Norton & Company.

Fletcher, K., Nutton, J., & Brend, D. (2015). Attachment, a matter of substance: The potential

of attachment theory in the treatment of addictions. Clinical Social Work Journal,

43(1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0502-5

Ford, J. D., Spinazzola, J., van der Kolk, B., & Grasso, D. J. (2018). Toward an empirically based developmental trauma disorder diagnosis for children: Factor structure, item characteristics, reliability, and validity of the developmental trauma disorder semi-structured interview. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(5). https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.17m11675

Ford, K., & Garzon, F. (2017). Research note: A randomized investigation of evangelical Christian accommodative mindfulness. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 4(2),

92-99. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000137

Foroughe, M. F., & Muller, R. T. (2014). Attachment-based intervention strategies in family therapy with survivors of intra-familial trauma: A case study. Journal of Family Violence, 29(5), 539-548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9607-4

Frederick, T., & White, K. M. (2015). Mindfulness, Christian devotion, meditation, surrender, and worry. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 18(10), 850-858. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2015.1107892

Freyd, J. J., Deprince, A. P., & Gleaves, D. H. (2007). The state of betrayal trauma theory:

Reply to McNally. Conceptual issues, and future directions. Memory, 15(3),

295-311. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658210701256514

Garzon, F., & Ford, K. (2016). Adapting mindfulness for conservative Christians.

The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 35(3), 263.

Garzon, F., & Poloma, M. (2005). Theophostic ministry: Preliminary practitioner survey. Pastoral Psychology, 53(5), 387-396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-005-2582-1

Garzon, F., & Tilley, K. A. (2009). Do lay Christian counseling approaches work?

What we currently know. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 28(2), 130.

Geisler, N. (1992). Miracles and the modern mind: A defense of biblical miracles.

Baker Book House.

Gerritsen, R. J. S., & Band, G. P. H. (2018). Breath of life: The respiratory vagal stimulation model of contemplative activity. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 12, 397-397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2018.00397

Gingrich, D. H. (2013). Restoring the shattered self: A Christian counselor’s guide to complex trauma. IVP Academic.

Glenn, C. T. B. (2014). A bridge over troubled waters: Spirituality and resilience with emerging adult childhood trauma survivors. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 16(1), 37-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2014.864543

Glück, T. M., Knefel, M., Tran, U. S., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2016). PTSD in ICD-10 and proposed ICD-11 in elderly with childhood trauma: Prevalence, factor structure, and symptom profiles. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.29700

Gobin, R. L., & Freyd, J. J. (2014). The impact of betrayal trauma on the tendency to trust. Psychological Trauma, 6(5), 505-511. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032452

Goldner, L., Sachar, S. C., & Abir, A., (2019). Mother-adolescent parentification, enmeshment, and adolescents’ intimacy: The mediating role of rejection sensitivity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(1), 192-201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1244-8

Gómez, J. M., Lewis, J. K., Noll, L. K., Smidt, A. M., & Birrell, P. J. (2016). Shifting the focus: Nonpathologizing approaches to healing from betrayal trauma through an emphasis on relational care. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17(2), 165-185. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2016.1103104

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E., Gould, N., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D., Shihab, H., Ranasinghe, P., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E.,

Haythornthwaite, J., & Cramer, H. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Deutsche Zeitschrift Für Akupunktur [German Magazine for Acupuncture], 57(3), 26-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dza.2014.07.007

Gulden, A. W., & Jennings, L. (2016). How yoga helps heal interpersonal trauma: Perspectives and themes from 11 interpersonal trauma survivors. International Journal of Yoga Therapy, 26(1), 21-31. https://doi.org/10.17761/1531-2054-26.1.21

Halberstein, R., DeSantis, L., Sirkin, A., Padron-Fajardo, V., & Ojeda-Vaz, M. (2007). Healing with Bach® flower essences: Testing a complementary therapy. Complementary Health Practice Review, 12(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533210107300705

Hann-Morrison, D. (2012). Maternal enmeshment: The chosen child. SAGE Open, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244012470115

Harris, J. I., Erbes, C. R., Engdahl, B. E., Olson, R. H. A., Winskowski, A. M., & McMahill, J. (2008). Christian religious functioning and trauma outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20427

Hartelius, G. (2017). Taylor’s soft perennialism: Psychology or new age spiritual vision? International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 36(2), 136-146. https://doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2017.36.2.136

Hathaway, W., & Tan, E. (2009). Religiously oriented mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(2), 158-171. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20569

Haxhe, S. (2016). Parentification and related processes: Distinction and implications

for clinical practice. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 27(3), 185-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2016.1199768

Heiden-Rootes, K. M., Jankowski, P. J., & Sandage, S. J. (2010). Bowen family systems

theory and spirituality: Exploring the relationship between triangulation and religious questing. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(2), 89-101.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-009-9101-y

Heller, L., & LaPierre, A. (2012). Healing developmental trauma: How early trauma affects

self-regulation, self-image, and the capacity for relationship. North Atlantic Books.

Herman, J. (2012). C-PTSD is a distinct entity: Comment on Resnick et al. (2012).

Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 256-257. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21697

Hocking, E. C., Simons, R. M., & Surette, R. J. (2016). Attachment style as a mediator

between childhood maltreatment and the experience of betrayal trauma as an adult.

Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 94-101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.01.001

Hook, J. N., & Worthington, E. L. (2009). Christian couple counseling by professional, pastoral, and lay counselors from a protestant perspective: A nationwide survey. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 37(2), 169-183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180802151760

Hooper, L. M. (2007). The application of attachment theory and family systems theory to the phenomena of parentification. The Family Journal, 15(3), 217-223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480707301290

Hoover, J. (2018). Can Christians practice mindfulness without compromising their convictions? The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 37(3), 247-255.

Hughes, D. (2017). Dyadic developmental psychotherapy (DDP): An attachment‐focused family treatment for developmental trauma. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 38(4), 595-605. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1273

Hull, A., Holliday, S. B., Eickhoff, C., Rose-Boyce, M., Sullivan, P., & Reinhard, M. (2015). The integrative health and wellness program: Development and use of a complementary and alternative medicine clinic for veterans. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 21(6), 12-21. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

Isobel, S., Goodyear, M., & Foster, K. (2019). Psychological trauma in the context of familial relationships: A concept analysis. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017726424

Jaebong, B., & Kwajik, L. (2016). Pastoral counseling understanding of Jacob’s dysfunction and its healing process: Focused on Bowen’s theory of family therapy. Korean Evangelical Theological Society, 79, 91-132. Retrieved from https://www.ataasia.com/portfolio_category/korea/

Jain, A. R. (2012). The malleability of yoga: A response to Christian and Hindu opponents

of the popularization of yoga. Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 25(4). https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1510

Jain, A. R. (2014). Who is to say modern yoga practitioners have it all wrong? On Hindu

origins and yogaphobia. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 82(2), 427-471. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lft099

Jain, A. R. (2017). Yoga, Christians practicing yoga, and God: On theological compatibility,

or is there a better question? Journal of Hindu-Christian Studies, 30(6). https://doi.org/10.7825/2164-6279.1658

Jain, S., Hammerschlag, R., Mills, P., Cohen, L., Krieger, R., Vieten, C., & Lutgendorf, S. (2015). Clinical studies of biofield therapies: Summary, methodological challenges,

and recommendations. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 4(Suppl), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2015.034.suppl

Jindani, F., & Khalsa, G. F. S. (2015). A journey to embodied healing: Yoga as a treatment

for post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work 34(4), 394-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2015.1082455

Johnson, E. L., Knabb, J. J., & Garzon, F. (2020). Conclusion to the special issue: Formalizing Christian indigenous practices for evidence-based research. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 39(1), 75-85.

Jones, T. L., Garzon, F. L., & Ford, K. M. (2021). Christian accommodative mindfulness in the clinical treatment of shame, depression, and anxiety: Results of an N-of-1 time-series study. Spirituality in Clinical Practice [advance online publication]. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000221

Jowett, S., Karatzias, T., & Albert, I. (2019). Multiple and interpersonal trauma are risk factors for both post‐traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder: A systematic review on the traumatic backgrounds and clinical characteristics of comorbid post‐traumatic stress disorder/borderline personality disorder groups versus single‐disorder groups. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 93(3), 621-638. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12248

Jung, C. G., Rossi, S., & Grice, L. K. (2018). Jung on astrology. Routledge.

Khafi, T. Y., Yates, T. M., & Sher-Censor, E. (2015). The meaning of emotional overinvolvement in early development: Prospective relations with child behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(4), 585-594. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000111

Klassen, P. E. (2005). Ritual appropriation and appropriate ritual: Christian healing and adaptations of Asian religions. History and Anthropology, 16(3), 377-391. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757200500219313

Knabb, J. J. (2012). Centering prayer as an alternative to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression relapse prevention. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 908-924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9404-1

Knabb, J. J., & Bates, M. T. (2020). “Holy desire” within the “cloud of unknowing”: The psychological contributions of medieval apophatic contemplation to Christian mental health in the 21st century. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 39(1), 24-39.

Knabb, J. J., & Emerson, M. Y. (2013). “I will be your God and you will be my people”: Attachment theory and the grand narrative of scripture. Pastoral Psychology, 62(6),

827-841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-012-0500-x

Knabb, J. J., Johnson, E. L., & Garzon, F. (2020). Introduction to the special issue: Meditation, prayer, and contemplation in the Christian tradition: Towards the operationalization and clinical application of Christian practices in psychotherapy and counseling.

The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 39(1), 5-11.

Knabb, J. J., Vazquez, V., Garzon, F. L., Ford, K. M., Wang, K. T., Conner, K. W., Warren, S. E., & Weston, D. M. (2020). Christian meditation for repetitive negative thinking:

A multisite randomized trial examining the effects of a 4-week preventative program. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 7(1), 34-50. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000206

Knabb, J. J., Vazquez, V., & Pate, R. (2019). “Set your minds on things above”: Shifting from trauma-based ruminations to ruminating on God. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 22(4), 384-399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2019.1612336

Knabb, J. J., Vazquez, V. E., Pate, R. A., Garzon, F. L., Wang, K. T., Edison-Riley, D., Slick, A. R., Smith, R. R., & Weber, S. E. (2021). Christian meditation for trauma-based rumination: A two-part study examining the effects of an internet-based 4-week program. Spirituality in Clinical Practice [advance online publication]. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000255

Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature in psychiatry. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 269. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00269

Lad, V. (2009). Ayurveda, the science of self-healing: A practical guide. Lotus Press.

Langberg, D. (2003). Counseling survivors of sexual abuse. Xulon Press.

Lange-Altman, T., Bergandi, T., Borders, K., & Frazier, V. (2017). Seeking safety and the 12-step social model of recovery: An integrated treatment approach. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 12(1), 13-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1556035X.2016.1258682

Levers, L. L. (2012). Trauma counseling: Theories and interventions. Springer Publications.

Liu, C., Beauchemin, J., Wang, X., & Lee, M. Y. (2018). Integrative body-mind-spirit (I-BMS) interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A review of the outcome literature. Journal of Social Service Research, 44(4), 482-493. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2018.1476299

Lombard, C. A. (2017). Psychosynthesis: A foundational bridge between psychology and spirituality. Pastoral Psychology, 66(4), 461-485.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-017-0753-5

Love, P., & Robinson, J. (1991). The emotional incest syndrome: What to do when a parent’s love rules your life. Bantam Books.

Love, P., & Shulkin, S. (2001). Imago theory and the psychology of attraction. The Family Journal, 9(3), 246-249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480701093002

Lowyck, B., Luyten, P., Demyttenaere, K., & Corveleyn, J. (2008). The role of romantic attachment and self‐criticism and dependency for the relationship satisfaction of community adults. Journal of Family Therapy, 30(1), 78-95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2008.00417.x

Macy, R. J., Jones, E., Graham, L. M., & Roach, L. (2018). Yoga for trauma and related mental health problems: A meta-review with clinical and service recommendations. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015620834

Malchiodi, C. A. (2012). Trauma and expressive arts therapy: Brain, body, and imagination

in the healing process. Guilford Press.

Mandeville, R. (2021). Rejected, shamed, and blamed: Help and hope for adults in the family scapegoat role. Self-published.

Mangione, L., Swengros, D., & Anderson, J. G. (2017). Mental-health wellness and biofield therapies: An integrative review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(11), 930-944. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1364808

Marotta-Walters, S. A., Jain, K., DiNardo, J., Kaur, P., & Kaligounder, S. (2018). A review

of mobile applications for facilitating EMDR treatment of complex trauma and its comorbidities. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 12(1), 2-15. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.12.1.2

Maximos [Metropolitan Maximos Aghiorgoussis]. (1999). The challenge of metaphysical experiences outside orthodoxy and the orthodox response. The Greek Orthodox Theological Review, 44(1), 21. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

May, G. G. (1974). The psychodynamics of spirituality. The Journal of Pastoral Care,

28(2), 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234097402800203

McClure, B. J. (2010). The social construction of emotions: A new direction in the pastoral

work of healing. Pastoral Psychology, 59(6), 799-812.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-010-0301-z

McManus, D. E. (2017). Reiki is better than placebo and has broad potential as a complementary health therapy. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 22(4) 1051-1057. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587217728644

Means, J. J. (1997). Pastoral counseling: An alternative path in mental health. The Journal

of Pastoral Care, 51(3), 317-328. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234099705100307

Miller, R. C. (2015). The iRest program for healing PTSD: A proven-effective approach to

using Yoga Nidra meditation & deep relaxation techniques to overcome trauma.

New Harbinger.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Harvard University Press.

Mitchell, K. R., & Anderson, H. (1981). You must leave before you can cleave: A family systems approach to premarital pastoral work. Pastoral Psychology, 30(2), 71-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01033061

Mohi-Ud-Din, M., & Pandey, M. (2018). Impact of yoga nidra on the personality of drug addicts. Indian Journal of Health and Well-being, 9(5), 758-760. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

Moon, K., Brewer, T. D., Januchowski-Hartley, S. R., Adams, V. M., & Blackman, D. A. (2016). A guideline to improve qualitative social science publishing in ecology and conservation journals. Ecology and Society, 21(3), 17. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08663-210317

Neumann, D. J. (2019). “Development of body, mind, and soul:” Paramahansa Yogananda’s marketing of yoga-based religion. Religion and American Culture, 29(1), 65-101. https://doi.org/10.1017/rac.2018.4

Nguyen-Feng, V. N., Morrissette, J., Lewis-Dmello, A., Michel, H., Anders, D., Wagner, C., & Clark, C. J. (2019). Trauma-sensitive yoga as an adjunctive mental-health treatment for survivors of intimate partner violence: A qualitative examination. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 6(1), 27-43. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000177

Njus, D. M., & Okerstrom, K. (2016). Anxious and avoidant attachment to God predict moral foundations beyond adult attachment. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 44(3),

230-243. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164711604400305

Novak, J. R., Sandberg, J. G., & Davis, S. Y. (2017). The role of attachment behaviors in the link between relationship satisfaction and depression in clinical couples: Implications for clinical practice. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43(2), 352-363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12201

O’Farrell, T. J., Murphy, M., Alter, J., & Fals-Stewart, W. (2010, January). Behavioral family counseling for substance abuse: A treatment development pilot study. Addictive Behaviors, 35(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.003

Ong, I. (2021). Treating complex trauma survivors: A trauma-sensitive yoga (TSY)-informed psychotherapeutic approach. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 16(2), 182-195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2020.1761498

Ong, I., Cashwell, C. S., & Downs, H. A. (2019). Trauma-sensitive yoga: A collective case study of women’s trauma recovery from intimate partner violence. Counseling Outcome Research and Evaluation, 10(1), 19-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501378.2018.1521698

Öztürk, A., & Mutlu, T. (2010). The relationship between attachment style, subjective well-being, happiness, and social anxiety among university students. Procedia, Social, and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1772-1776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.398

Pan, P. J. D., Deng, L. F., Tsai, S. L., & Yuan, J. S. S. (2013). Issues of integration in psychological counseling practice from pastoral counseling perspectives.

The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 32(2), 146.

Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S. E., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. L. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis. Sage.

Pedersen, C. G., Christensen, S., Jensen, A. B., & Zachariae, R. (2013). In God and CAM we trust. Religious faith and use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of women treated for early breast cancer. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(3), 991-1013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9569-x

Pence, P. G., Katz, L. S., Huffman, C., & Cojucar, G. (2014). Delivering integrative restoration-yoga nidra meditation (iRest®) to women with sexual trauma at a veteran’s medical center: A pilot study. International Journal of Yoga Therapy, 24(1), 53-62. https://doi.org/10.17761/ijyt.24.1.u7747w56066vq78u

Peng, W., Liu, Z., Liu, Q., Chu, J., Zheng, K., Wang, J., Wei, H., Zhong, M., Ling, Y., & Yi, J. (2021). Insecure attachment and maladaptive emotion regulation mediating the relationship between childhood trauma and borderline personality features.

Journal of Depression & Anxiety, 38(1), 28-39. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23082

Platt, M. G., & Freyd, J. J. (2015). Betray my trust, shame on me: Shame, dissociation,

fear, and betrayal trauma. Psychological Trauma, 7(4), 398-404. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000022

Prest, L. A., Benson, M. J., & Protinsky, H. O. (1998). Family of origin and current relationship influences on codependency. Family Process, 37(4), 513-528. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1998.00513.x

Rahim, M. (2014). Developmental trauma disorder: An attachment-based perspective.

Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19(4), 548-560. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104514534947

Rambo, S. (2010). Trauma and faith: Reading the narrative of the hemorrhaging woman. International Journal of Practical Theology, 13(2), 233-257. https://doi.org/10.1515/IJPT.2009.15

Rasmussen, I. S., Arefjord, K., Winje, D., & Dovran, A. (2018). Childhood maltreatment trauma: A comparison between patients in treatment for substance use disorders and patients in mental-health treatment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1492835

Reinert, K. G., Campbell, J. C., Bandeen-Roche, K., Lee, J. W., & Szanton, S. (2016). Erratum to: The role of religious involvement in the relationship between early trauma and health outcomes among adult survivors. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 9(3), 181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-016-0113-0

Rosales, A., & Tan, S. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): Empirical evidence and clinical applications from a Christian perspective. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 35(3), 269.

Rosales, A., & Tan, S. (2017). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Empirical evidence and clinical applications from a Christian perspective. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 36(1), 76.

Roth, K., & Friedman, F. (2003). Surviving a borderline parent: How to heal your childhood wounds, & build trust, boundaries, and self-esteem. New Harbinger.

Rubinart, M., Fornieles, A., & Deus, J. (2017). The psychological impact of the Jesus prayer among non-conventional Catholics. Pastoral Psychology, 66(4), 487-504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-017-0762-4

Sahdra, B. K., Shaver, P. R., & Brown, K. W. (2010). A scale to measure nonattachment:

A Buddhist complement to western research on attachment and adaptive functioning. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(2), 116-127. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890903425960

Schimmenti, A. (2012). Unveiling the hidden self: Developmental trauma and pathological shame. Psychodynamic Practice, 18(2), 195-211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14753634.2012.664873

Schindler, A. (2019). Attachment and substance use disorders: Theoretical models, empirical evidence, and implications for treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00727

Schouten, K. A., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. M. (2015). The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults:

A systematic review on art therapy and trauma. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse,

16(2), 220-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838014555032

Sears, R. W., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118691403

Sebastian, B., & Nelms, J. (2017). The effectiveness of emotional freedom techniques in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Explore, 13(1),

16-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2016.10.001

Shaver, P. R., Schachner, D. A., & Mikulincer, M. (2005). Attachment style, excessive reassurance seeking, relationship processes, and depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(3), 343-359. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461616720421709

Sheinbaum, T., Bifulco, A., Ballespí, S., Mitjavila, M., Kwapil, T. R., & Barrantes-Vidal, N. (2015). Interview investigation of insecure attachment styles as mediators between

poor childhood care and schizophrenia-spectrum phenomenology. PloS One, 10(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135150

Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Fyvie, C., Roberts, N., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., & Cloitre, M. (2017). Alternative models of disorders of traumatic stress based on the

new ICD‐11 proposals.Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 135(5), 419-428. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12695

Siegel, I. R. (2018). EMDR as a transpersonal therapy: A trauma-focused approach to

awakening consciousness. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 12(1), 24-43. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.12.1.24

Siverns, K., & Morgan, G. (2019). Parenting in the context of historical childhood trauma:

An interpretive meta-synthesis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104186

Smith, J. A., Greer, T., Sheets, T., & Watson, S. (2011). Is there more to yoga than exercise? Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 17(3), 22-29. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

Snyder, R., Shapiro, S., & Treleaven, D. (2012). Attachment theory and mindfulness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(5), 709-717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9522-8

Spinazzola, J., der Kolk, B., & Ford, J. D. (2018). When nowhere is safe: Interpersonal trauma and attachment adversity as antecedents of posttraumatic stress disorder and developmental trauma disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(5), 631-642. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22320

Stephens, T., & Aparicio, E. M. (2017). “It’s just broken branches”: Child welfare-affected mothers’ dual experiences of insecurity and striving for resilience in the aftermath of complex trauma and familial substance abuse. Children and Youth Services Review,

73, 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.11.035

Stockham-Ronollo, S., & Poulsen, S. S. (2012). Couple therapy and Reiki: A holistic therapeutic integration. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480712449130

Stone, H. W. (1994). Brief pastoral counseling: Short-term approaches and strategies.

Fortress Press.

Strong, J. (1890). Strong’s exhaustive concordance of the Bible. Abingdon Press.

Tan, S. (2011). Counseling and psychotherapy: A Christian perspective. Baker Academic.

Tan, S. (2016). Lay counseling: Equipping Christians for a helping ministry. Zondervan.

Telles, S., Singh, N., & Balkrishna, A. (2012). Managing mental-health disorders resulting from trauma through yoga: A review. Depression Research and Treatment, 9, 401-513. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/401513

Uhernik, J. A. (2017). Using neuroscience in trauma therapy, creative and compassionate counseling. Routledge.

Ulaş, E., & Ekşi, H. (2019). Inclusion of family therapy in rehabilitation program of substance abuse and its efficacious implementation. The Family Journal, 27(4), 443-451. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480719871968

Vancampfort, D., Vansteelandt, K., Scheewe, T., Probst, M., Knapen, J., De Herdt, A., & De Hert, M. (2012). Yoga in schizophrenia: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials.Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 126(1), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01865.x

Van der Kolk, B. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

Van der Kolk, B., & Courtois, C. A. (2005). Editorial comments: Complex developmental trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(5), 385-388. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20046

Van Kanegan, G., & Worley, J. (2018). Complementary alternative and integrative treatment

for substance use disorders. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(6), 16-21. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20180521-04

Van Ness, P. (1999). Yoga as spiritual but not religious: A pragmatic perspective. American Journal of Theology & Philosophy, 20(1), 15-30. Retrieved from https://www.liberty.edu/library/

Van Nieuwenhove, K., & Meganck, R. (2019). Interpersonal features in complex trauma etiology, consequences, and treatment: A literature review. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(8), 903-928. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2017.1405316

Varambally, S., & Gangadhar, B. N. (2020). Yoga for psychiatric disorders: From fad

to evidence-based intervention? British Journal of Psychiatry, 216(6), 291-293. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.249

Vazquez, V. E., & Jensen, G. R. (2020). Practicing the Jesus prayer: Implications for psychological and spiritual well-being. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 39(1), 65-74.

Viola, F., & Barna, G. (2012). Pagan Christianity? Exploring the roots of our church practices. BarnaBooks.

Wang, D. C., & Tan, S. (2016). Dialectical behavior therapy: Empirical evidence and clinical applications from a Christian perspective. The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 35(1), 68.

Warren, E. J. (2018). Alternative medicine in North America: A Christian pastoral response.

The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 72(1), 22-31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305018754794

Webster, L. C., Holden, J. M., Ray, D. C., Price, E., & Hastings, T. M. (2020). The impact

of psychotherapeutic Reiki on anxiety. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health,

15(3), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2019.1688214

Wei, M., Shaffer, P. A., Young, S. K., & Zakalik, R. A. (2005). Adult attachment, shame, depression, and loneliness: The mediation role of basic psychological needs satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(4), 591-601. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.4.591

West, J., Liang, B., & Spinazzola, J. (2017). Trauma sensitive yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(2), 173-195. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000040

Whiffen, V. E., Kallos-Lilly, A. V., & MacDonald, B. J. (2001). Depression and attachment

in couples. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25(5), 577-590. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005557515597

Willis, K., Miller, R. B., Yorgason, J., & Dyer, J. (2020). Was Bowen correct? The relationship between differentiation and triangulation. Contemporary Family Therapy, 43(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-020-09557-3

Wright, J. G. (2006). An experimental study of the effects of remote intercessory prayer on depression [Doctoral dissertation, Liberty University]. Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/50

Zeugin, B. (2017). Is CAM religious? The methodological problems of categorizing complementary and alternative medicine in the study of religion. Bulletin for

the Study of Religion, 46(1), 6-8. https://doi.org/10.1558/bsor.30967

Zwissler, L. (2011). Second nature: Contemporary pagan ritual borrowing in progressive Christian communities. Canadian Woman Studies, 29(1-2), 16. Retrieved from https://cws.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/cws

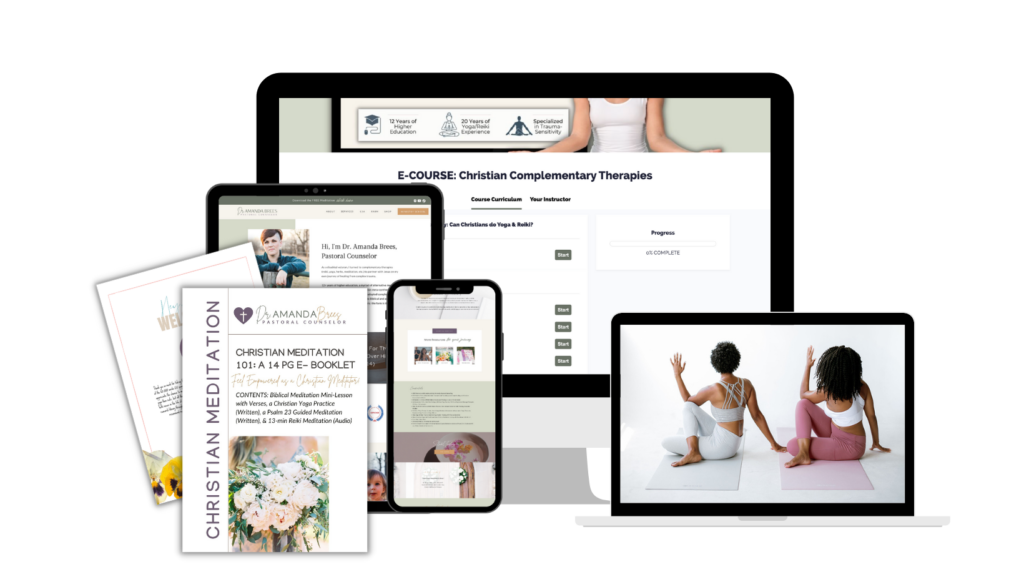

Want to learn more about Christian meditation? Take the course!

References

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

*Please note that all of these blog posts are reposts of my already published dissertation and are subject to copyright.

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment