| “In summary, in this section, we have learned more about Centering Prayer by comparing it with mindfulness, a well-researched mindful practice. First, we notice that both types of contemplation have a similar goal; that is, helping practitioners wake up to who they are” (Blanton, 2011, p. 140). |

| “Mindfulness and Centering Prayer both share the goal of obtaining a special connection. The emphasis in mindfulness is upon connecting with the present moment. Accomplishing this goal through mindfulness opens great possibilities for the practitioner. In contrast, Centering Prayer draws attention to a person’s union with God. Having made this distinction, both Centering Prayer and mindfulness highlight the present moment. Mindfulness teaches that we only have the present experience, while the practice of Centering recognizes that God resides in the current moment” (Blanton, 2011, p. 140). |

| “Additional practices have been developed in the Church since then, but with much the same differentiating purpose, like lectio Divina (sacred reading), meditation of various kinds (some based on discursive content, some not, and some a combination), prayer of various kinds (mental, affective, conversational, contemplative, imaginal, liturgical, and centering), recollection, detachment, purgation, illumination, union, mortification, vivification, renunciation, resignation, surrender, self-denial, transparency, watchfulness, the praise of God, gratitude to God, and communion with God” (Johnson et al., 2020, p. 81). |

| “”Neuroscientific studies clearly demonstrate that a focus on contemplative spiritual practice and mindfulness meditation has the capacity to increase our non-anxious awareness and therefore significantly lower our stress than does a focus on “right belief” or correct doctrine. As such, not only do these findings have important implications for pastoral counselors and psychotherapists, they perhaps will even necessitate a paradigm shift in the way that clergy approaches the general pastoral care of souls” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 552). |

| “The paradigmatic turn, however, toward neurotheology and the revolutionary discovery of neuroplasticity will necessitate a reordering of pastoral and clinical priorities, for it reveals rather precisely that through the daily spiritual practice of contemplative prayer and mindfulness meditation we can begin to literally ‘resculpt’ the neural pathways of the brain” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 554). |

| “Enduring high levels of suffering may be another important factor in adherence to the Jesus Prayer. P1 found that the Jesus Prayer provided her with something that her Zen meditation practice did not: feeling a presence that protected her and deeply comforted her. A theistically oriented meditative practice like the Jesus Prayer is designed to foster not only intrapersonal attunement but also interpersonal attunement with a divine entity. Although both forms of attunement are experienced at subjective levels and . . . both engage the same brain regions, attunement with the Divine may involve other qualities worthy of further in-depth exploration” (Rubinart et al., 2017, p. 501). |

| “This concurrence suggests that the improvement in Phobic Anxiety and Interpersonal Sensitivity could have been due to the Jesus Prayer’s strong mindfulness component rather than to merely trusting a higher power. Studies have shown that developing mindfulness skills through meditation practices involves the activation and further development of prefrontal regions of the brain . . . Relatedly . . . interpersonal neurobiology to study attachment mechanisms to explain the benefits of mindfulness practices. This author has noted that both secure attachment and mindfulness involve the development of integrative regions in the middle prefrontal cortex that are responsible for self-regulation and emotional balance” (Rubinart et al., 2017, p. 500). |

| “However, prior to the Centering Prayer, an ancient meditative prayer also based on the teachings of the Desert Fathers had been developed and practiced for centuries. This prayer, known as the Jesus Prayer or the Prayer of the Heart . . . consists of unceasingly invoking Jesus Christ’s presence with great attention and sincerity, from one’s heart, and asking Him for mercy . . . Thought of as the very means to become united with the Divine, the Jesus Prayer is also described as being of great help for purifying one’s heart . . . which, in psychological terms, can be explained as a means for transforming and healing one’s personality. The art and science of the Jesus Prayer and the spiritual teachings around this prayer have been developed and preserved by the Hesychasm, an ancient Christian mystical tradition that was later absorbed by the Orthodox Christian Church . . . Deeply devotional, highly spiritual” (Rubinart et al., 2017, p. 489). |

| “A meta-analysis on different forms of meditation pointed to the fact that there were no such differences but, rather, that each form of meditation yielded stronger effects within different domains. Mindfulness meditation proved to be superior for treating personality disorders, reducing stress, and improving attention, whereas transcendental meditation was superior for reducing negative emotions, trait anxiety, and neuroticism, as well as for strengthening learning and memory . . . Therefore, more research addressing the spiritual component of each form of meditation needs to be conducted” (Rubinart, et al., 2017, p. 488). |

“This monitoring of awareness and intention is at the heart of all mindfulness practices, from yoga to insight meditation, whether the focus is on posture and movement, the breath, a candle flame, or any of the myriad other targets found in the world’s cultures . . . A fundamental purpose of all meditational practices, whatever the particular faith tradition, is to anchor and stabilize our awareness in order to decouple automaticity and reactivity in the mind, which in turn will foster neuroplasticity in the brain” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 556). |

| “Ignatius suggests and/or to engage in mindfulness breathing meditation has the capacity over time to change the brain by developing a ‘stabilized awareness of the mind to achieve mental equilibrium’ . . . This is the promise of neuroplasticity” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 556). |

| “The twin discoveries of neuroplasticity and the fact that it can to some extent be self-directed through contemplative spiritual practice and mindfulness meditation now gives clearer insight and direction to pastoral practitioners wanting to make more informed and effective interventions. This is not at all to suggest that a focus on religious beliefs and doctrines” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 555). |

| “First, centering prayer is a way to get in touch with the center of being so as to experience intimate union with God: ‘In centering prayer we are going beyond thought and image, beyond the senses and the rational mind, to that center of our being where God is working a wonderful work’” (Knabb, 2012, p. 914). |

| “The results of this study indicate that surrender, a key component of centering prayer, provides an empirical link for incorporating the benefits of mindfulness for Christians” (Frederick & White, 2015, p. 850). |

| “Recent empirical findings suggest nonattachment mediates the link between mindfulness and a range of psychological outcomes, including well-being, depression, anxiety, and stress . . . as well as life satisfaction” (Knabb, Vazquez, et al., 2020, p. 35). |

| “As Christians turn from inner and outer preoccupations to humbly reaching out to God, they may be able to effectively detach from daily worries and concerns, including an overemphasis on the self. In other words, humble detachment may allow Christians to successfully pivot from an anxious, distracted inner focus to surrendering to God, moment-by-moment. In utilizing both kataphatic (scriptural) and apophatic (contemplative) forms of Christian mediation, these practices may help individuals to separate themselves from the ruminations and worries of this world by repeatedly shifting from the ‘self’ to the ‘Other.’” (Knabb, Vazquez, et al., 2020, p. 47). |

“Compared the effectiveness of a traditional CBT protocol with a Christian CBT protocol, finding that while both were effective in reducing symptoms of depression, the accommodated CBT resulted in greater improvements on measures of spiritual well-being in a religious sample” (K. Ford & Garzon, 2017, p. 92). |

| “Above and beyond developing a deeper awareness of the present moment, mindfulness meditation is more fundamentally a form of a healthy relationship with oneself” (Bingaman, 2011, p. 480). |

| “Reflection on the nature of one’s own mental processes is a form of metacognition, thinking about thinking in the broadest sense; when we have meta-awareness this indicates awareness of awareness. Whether we are engaging in yoga or Centering Prayer, sitting and sensing our breathing in the morning, or doing tai chi at night, each mindful awareness practice develops this capacity to be aware of awareness” (Bingaman, 2011, p. 482). |

| “While the Buddhist practice of mindfulness meditation would seem to be the perfect fit for neuroscientists interested in how to modify the brain for the better, other contemplative spiritual practices from a variety of religious traditions have a similar capacity to build up new neural structure . . . whether we are engaging in Eastern forms of spiritual practice, such as yoga or tai chi, or in Western forms of contemplative prayer, or in practices common to both, namely meditation, we are immersing ourselves in any number of mindful awareness practices that have the capacity to help us become more metacognitively aware of our own awareness” Bingaman, 2011, p. 487). |

| “This ruminative style is problematic because when dysthymic moods are activated and the problem is understood to be within the self-and potentially unsolvable-depression is more likely to take hold” (Rosales & Tan, 2017, p. 77). |

| “In truth, the ability to lovingly guide one’s attention may be the foundation of all mindfulness practices, whether eastern or western, ancient or contemporary, religious or irreligious. Scripture repeatedly emphasizes the importance of focus and indicates the potentially destructive nature of distraction” (Hoover, 2018, p. 249). |

| “Jesus, knowing she was emotionally fragmented by stress and concern, graciously tried to redirect her focus. But the Lord said to her, ‘My dear Martha, you are worried and upset over all these details! There is only one thing worth being concerned about. Mary has discovered it, and it will not be taken away from her’ (Luke 10:41-42, New Living Translation). Here, Jesus indicates that distraction can cause both anxiety and emotional reactivity and that Mary’s focus shows an appreciation for what is most important within the present. This fits well with the characterization of mindfulness as switching modes from ‘doing’ to ‘being’” (Hoover, 2018, p. 249). |

| “At the deepest level, mindfulness is about freedom: freedom from reflexive patterns, freedom from reactivity, and ultimately, freedom from suffering . . . From a neurological standpoint, the mindful approach helps reduce the limbic dominance that exists in individuals who might otherwise be reactive and given to neurotic interpretation of events” (Hoover, 2018, p. 252). |

| “The problem with cathartically working through residual feelings and attachments and/or engaging in disputation with irrational thoughts and attitudes is that in either case it is keeping unwanted thoughts and feelings active in the brain, far longer than they need to be” (Bingaman, 2015). |

| “In the context of mindfulness- and acceptance-based therapies, clients are encouraged to accept rather than resist or challenge their anxious thoughts and feelings, which correlates positively with a reduction in fearful limbic activity . . . neurobiological studies of meditation, a central feature of MBCT treatment that helps a client practice acceptance both inside and outside of the therapy session, have demonstrated that regular meditation practice literally reshapes one’s brain, leading to long-lasting changes in neural function . . . For pastoral and spiritual caregivers, the integration of mindfulness- and acceptance-based frames of reference with regular contemplative-meditational practice has the capacity to help clients and congregants reshape their mind and brain” (Bingaman, 2015, p. 578). |

| “The polyvagal theory . . . elaborates the neurophysiology of trauma responses and how trauma survivors using body-aware practices are able to access an evolved somatic capacity to be relationally connected when they re-experience life-threatening danger . . . The polyvagal theory legitimates the study of age-old collective and religious practices such as communal chanting, various breathing techniques, and other methods that cause shifts in autonomic states . . . Mindfulness meditation and yoga, for example, have proven to help trauma survivors identify and anticipate triggers and learn to ride out the emotional waves that accompany post-traumatic stress” (Doehring, 2019, p. 242). |

| “Embedded within a variety of contemporary treatment approaches, mindfulness-based interventions seek to ameliorate a wide range of trauma-related symptoms (e.g., hyperarousal, ruminative thoughts, intrusive memories) by helping practitioners cultivate awareness and attention, noticing their symptoms with non-judgment, then shifting their focus from symptom preoccupation and the ‘whys’ and ‘what ifs’ of trauma-related experiences to the breath and senses” (Knabb et al., 2019, p. 386). |

| “This deals with negation as a process of communing with God. We can call this a relational or communal distinction” (Knabb & Bates, 2020, p. 28). |

| “Although additional research is necessary, these initial studies suggest apophatic contemplative practice holds promise as a clinical intervention for several cognitive vulnerabilities” (Knabb & Bates, 2020, p. 36). |

| “This meditation, entitled ‘The Wisdom of Accepted Tenderness,’ supports the development of self-acceptance and self-compassion by focusing on God’s grace. In our work with clients, we find that cultivating this self-compassion is often the starting point that leads to the development of compassion for others later. Over the course of therapy, adapted meditations can weave both self-compassion and compassion for others themes together, but we chose Johnston’s tenderness meditation for this article because of the foundational initial importance of self-compassion” (Garzon & Ford, 2016, p. 265). |

| “The extraordinary advances in neuroscience in recent years have begun to influence the study of religion, theology, and spirituality. Indeed, the emerging fields of neurotheology and spiritual neuroscience reflect a growing interest in what neuroscientific studies reveal about what is most fundamental to religious faith and the spiritual life . . . focused on important neuroscientific findings regarding the plasticity and malleability of the human brain to make the case for greater use of contemplative and mindfulness meditation practices in pastoral care and counseling” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 549). |

| “This article continues the author’s exploration of the significance of recent neuroscientific research for pastoral care and counseling Bingaman…by focusing on the plasticity and malleability of the human brain. It makes the case for mindfulness meditation (e.g., Centering Prayer) as a means to lower activity in the amygdala and thereby calm the stress region of the brain. In light of evidence that such mindfulness practices are more effective in reducing anxiety than is a focus on right belief or correct doctrine the case is made for a paradigmatic turn . . . toward neurotheology, which seeks to understand the relationship between the brain and theology” (Bingaman, 2013, 549). |

| “The ‘promise of neuroplasticity’ has been articulated by such notable neuroscientists . . . the emerging field of neurotheology that focuses on the neuroscientific study of religious and spiritual experiences . . . helps us to see the possibilities for cultivating wellness and neural integration in daily life . . . ‘by harnessing the power of awareness to strategically stimulate the brain’s firing, mindsight enables us to voluntarily change a firing pattern that was laid down involuntarily’” (Bingaman, 2013, p. 550). |

| “The biblical story begins with Genesis 2, when God creates everything. The peak of Creation is humankind, made on the sixth day after everything else has been made, and most importantly made in God’s image. Much ink has been spilled over what the term image of God means, but it is apparent that a fundamental aspect of being made in the image of God is the quality of being relational” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 833). |

| “Thus, they attempt to become their own secure base and safe haven and turn away from the God-given design of relational interdependence. The result of their behavior, as seen in the curses of Genesis 3, is separation. Interestingly . . . due to the fall, humankind continuously experiences the emotion of shame as a reminder of this estrangement and separation from God” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 834). |

| “God is no longer their safe haven. The original design of interdependence is broken due to Adam and Even believing that they could be like God . . . rather than dependent on God for safety, sustenance, and protection. This pattern of separation from God, one another, and the rest of creation is seen not only in Genesis 3 with Adam and Eve, but through the entirety of Israel’s history. The story of Israel is a story of exile usually due to turning away from God and promised future restoration. The book of Judges, for instance, tells the story of Israel after the Israelites entered the Promised Land under Joshua, and it is a story of Israel continually turning away from and disobeying YHWH. Instead of exploring in proximity to their secure base, following YHWHs commands, worshiping only YHWH, and returning to YHWH as a safe haven” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 835). |

“The ultimate exilic event and one that mirrors Judges, Genesis 3, and a number of other foreshadowing events in Israel’s history is the Assyrian/Babylonian exile (2 Kings 1725). From Joshua through 2 Kings, Israel’s history has been marked with disobedience and idolatry. For example, in the book of Judges, YHWH sometimes punishes Israel for their sin, but they are never sent out of the land or totally destroyed. This reality changes in 2 Kings 1725due to their ongoing idolatry and disobedience, YHWH exiles them from the land, first using Assyria to conquer the Northern Kingdom of Israel, then using Babylon to conquer the Southern Kingdom of Judah. By 587 B.C., Israel no longer exists as an independent nation. They are scattered throughout Assyria and Persia, settling primarily in Babylon. In fact, they are disinherited from the land and disassociated from their kin,6 both signs that they are separated from YHWH. The ultimate sign of this separation is the destruction of the Temple by King” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 835). |

| “The hope of Lamentations, that God will one day restore God’s relationship with God’s people, is the hope of the entire Bible and the hope of its narrative” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 835). |

| “The ultimate benefit of salvation that is affirmed over and over in the biblical narrative is that it brings humanity back into harmonious relationship with God, with one another (their brothers and sisters in Christ), and with the rest of creation. Salvation is essentially reunification, or re-attachment, returning to God in the center of the Garden as a secure base and safe haven, continuously maintaining proximity to God (e.g., seeking God’s will, following Gods commands) and signaling to God (e.g., reaching out, crying out) in times of need” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 836). |

| “Jesus accomplishes re-attaching those who believe in Jesus with God through Jesus own death and resurrection, where Jesus pays the penalty for sin on the cross by defeating death, Hell, and the grave and gives new life through his resurrection” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 837). |

| “Ultimately, this picture of re-attachment is seen in Revelation 21 and 22, where believing humanity dwells together in God’s new heavens and new earth with God. Believing humans are reunited with one another, with the restored creation, and with God, returning to the circle of attachment that is needed for physical, psychological, and spiritual survival. The refrain of the Old Testament is repeated once more in Revelation 21:3: And, I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. The biblical story, then, tells us that humankind was originally made to dwell with God, their secure base, and to explore God’s world through cultivating and keeping the Garden while staying within proximity of God’s word (i.e., commands) and returning to God as a safe haven in times of need” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 838). |

| “In this final section, we argue that therapists and pastoral counselors can significantly improve their interventions by integrating the attachment theory empirical base with God’s story for the restoration of relational unity. Thus, we offer three suggestions for therapists and pastoral counselors in their work with Christian clients, including (a) an integrative assessment strategy, (b) helping Christian clients to narrate their God attachment story, and (c) utilizing the therapist-client relationship as a corrective secure base and safe haven so as to deepen client’s attachment to God as the perfect attachment figure” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 838). |

| “Background of the client’s most important relationships, dating back to childhood. Included in this exploration will be an account of the client’s relationship with his or her parents, as well as a review of his or her relationships with important caregivers and mentors throughout childhood” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 838). |

| “Regarding the four styles of attachment, a secure attachment pattern involves a positive view of self and other, with the client possessing healthy self-esteem and believing that other people are dependable, trustworthy, and supportive . . . A preoccupied pattern indicates that the individual has a positive view of others, seeing them as inherently dependable and trustworthy, but a negative view of self, such that the individual doubts that others will be available due to his or her lack of self-worth . . . third category, the fearful attachment style, illuminates a negative view of both self and other, to where the individual doubts the value of him or herself and doubts that others are dependable, trustworthy, and safe. Finally, the dismissing style reveals someone who has considerable self-esteem but doubts that others are trustworthy and safe” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 839). |

| “As an example, a Christian client with a preoccupied style may have trouble believing that he or she is valuable in the eyes of God and, thus, question why God would pursue an intimate relationship with him or her. To be sure, a common theme among Christians with a preoccupied attachment style might be a feeling of inadequacy and shame. In turn, such Christians may struggle to accept God as a safe haven, believing that God might somehow turn away or reject them. Moreover, if they don’t feel that their need for intimacy is met, that is, if they don’t feel God’s closeness, they might experience a high degree of distress” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 839). |

| “As another example, the fearful attachment style may reveal that the Christian client doubts both his or her self-worth and God’s availability and dependability as a secure base and safe haven. If this is the case, the Christian might struggle to feel deeply connected to God, experiencing feelings of inadequacy and shame and, ultimately, doubt that God is trustworthy. Certainly, the fearful Christian might avoid intimacy with God altogether so as to avoid the psychological pain attached to perceived distance or rejection from God” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 839). |

“Exemplified in the perfect intimacy found in Jesus Christ” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 840). |

| “Pastoral psychologists can understand the Self as God’s consciousness and will and the BI as the full human being that we are all called to become in baptism. The idea that the Self is both universal and individual can be equated to the Christian understanding that we are all created in the image of God; that is, we all reflect the universal higher qualities of God through our unique individual identities. Spiritual psychosynthesis is the journey towards strengthening the I-Self relationship or, in Christian terms, our relationship to God. Relationship is one of the keys to all psychosynthesis work and is further discussed in the next section” (Lombard, 2017, p. 467). |

| “Spiritual meaning-making influences survivor resilience . . . This work begins with a reflection on the influence of sacred text interpretations and proceeds to address contextual considerations for pastoral counseling with emerging adult childhood trauma survivors” (Glenn, 2014, p. 37). |

| “Growing up is hard. This is especially the case for persons who experience childhood trauma through an act of abuse or neglect” (Glenn, 2014, p. 37). |

| “For survivors of childhood trauma, resilience appears in the fragile spaces between healing and devastation” (Glenn, 2014, p. 37). |

| “Pastoral counseling offers a sacred space that facilitates therapeutic healing and reparative relationships. In pastoral counseling, survivors who struggle to see the goodness in themselves can reclaim their splendor as a divinely created being, created in the Imago Dei (Image of God)” (Glenn, 2014, p. 38). |

| “Religious experimentation during this stage is expected as well as the wide-ranging rejection of previously held beliefs . . . For these reasons, it is important to explore emerging adult spirituality from a personal perspective” (Glenn, 2014, p. 44). |

| “A better characterization of college students would be ‘spiritual seekers’ who dismantle and reconstruct spiritual realities during early adulthood without the rigid boundaries of denominational religion. Studying emerging adult spirituality gives insight into their understanding of connectedness with a greater other and how the formation of that sense of connectedness influenced the protective frameworks they developed following trauma” (Glenn, 2014, p. 44). |

| “The discipline of pastoral counseling specializes in exploring the internal processes of connectedness between individuals and the divine. One guiding belief of pastoral counseling suggests that optimized engagement with one’s true self radiates from one’s reception to being enduringly connected with other humans and with the divine. In therapy, having a deeper awareness of being divinely connected to all others may serve as an entry point into a sense of belongingness for individuals who feel isolated due to the traumatic effects of childhood abuse or neglect” (Glenn, 2014, p. 48). |

“Research on institutional betrayal has found that institutional wrongdoing that fails to prevent or respond supportively to victims of abuse adds to the burden of trauma. In this two-study investigation with young adult university students, we demonstrated parallels between institutional betrayal and ways that families can fail to prevent or respond supportively to child abuse perpetrated by a trusted other, a phenomenon we call family betrayal (FB)” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 720). |

| “Survivors of child abuse have described unsupportive family reactions to abuse as ‘worse than the abuse itself’” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 721). |

| “In this study, informed by betrayal trauma theory…we propose a parallel phenomenon: family betrayal. We consider why and under what conditions family betrayal can occur, and test hypotheses about its potential long-term negative consequences” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 721). |

| “Trust and dependence are fundamental features of many close relationships that help explain why it can be particularly difficult for victims to acknowledge harm within these relationships . . . victims of abuse remaining largely unaware of their abuse” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 721). |

| “When victims trust and depend upon their perpetrators for caregiving or other resources— as a child trusts and depends on a parent, coach, or religious figure—confront-or-withdraw responses may jeopardize the needed relationship. In this case, diminished awareness of abuse, or ‘betrayal blindness,’ can be adaptive in that it decreases the likelihood that victims will alienate the perpetrator” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 721). |

| “With every one act of family betrayal by the family of origin, the young adults in this sample were 1.21 times more likely to exceed clinically significant levels of posttraumatic stress on the PCL-5, B = 0.19, Wald (1) = 12.15, p < .001, 95% CI for eB [1.09, 1.34]. Put another way, young adults who reported experiencing the sample mean number of acts/forms of family betrayal, 2.79 (SD = 4.00), were almost three and a half times as likely to report clinically significant levels of posttraumatic stress than young adults with no histories of family betrayal” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 736). |

| “Given the frequency with which family betrayal accompanied abuse by someone close to the victim (and therefore, likely close to the family), this finding in particular may help to explain the enduring effects of child abuse. In particular, beyond the exposure to family betrayal at the time of abuse (or when abuse is first disclosed), family systems theory suggests that the family itself may re-organize in an attempt to maintain homeostasis when exposed to a potentially disruptive force such as abuse” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 738). |

“With the phenomenon of family betrayal, bystanders are asked to lift an additional layer of the veil. This study has found that the family, where many assume that children can expect safety and protection from foreseeable harm, plays a role in enabling abuse for the majority of those abused in childhood. An urgent question for ongoing research is how family bystanders who depend on the perpetrator can be empowered to anticipate and respond supportively when a vulnerable member of the family has been abused” (Delker et al., 2018, p. 741). |

| “Instead, children move from relying on parents as a secure base and safe haven to leaning on a significant other in adulthood for psychological survival” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 828). |

| “Some family systems, however, cannot tolerate change. They will resist any member’s departure. Getting married is only acceptable if you do not leave home” (Mitchell & Anderson, 1981, p. 73). |

| “(a) the creation story in Genesis 12; (b) the effects of the severing of the attachment in the fall in Genesis 3 and in the subsequent exiles in Israel’s history; and (c) the primary goal of re-attachment in the redemptive promises to Israel and in the restoration begun with Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, culminating in His return in Revelation 21-22. In demonstrating the primacy of attachment to God both in the original creation and in the promised new creation, this section will illuminate the central tenets of attachment theory secure base, exploration, attachment behaviors (including protest, despair, and detachment), and safe haven embedded within the biblical storyline” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 833). |

| “Internal working model of relationships. Bowlby proposed that this internalized model of relationships forms early in life based on salient interpersonal interactions in childhood and is carried with the individual throughout the lifecycle and applied to adult relationships . . . This template of relationships is thought to serve the function of quickly helping the individual to make sense of relationships; however, roughly one third of children exhibit insecure attachment styles . . . suggesting that many children carry problematic templates of relationships into adulthood” (Knabb & Emerson, 2013, p. 839). |

| “Furthermore, the interreligious and intercultural exchanges–primarily between Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions–throughout the history of yoga in South Asia problematize the identification of yoga as Hindu” (Jain, 2014, p. 451). |

| “Yoga has a long history whereby adherents of numerous religions, including Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, Christian, and New Age traditions, have constructed, deconstructed, and reconstructed it anew. Symbols, practices and ideas vary across yoga studios and ashrams within the United States alone, thus illustrating that the quest for the essence of yoga is an impossible task” (Jain, 2014, p. 459). |

| “Yet, as converts to Christianity eventually (hopefully) learn, the mere knowledge of God, abstracted from the life and love of God, is inert, and it can eventually become destructive of the Christian life (which the archetypal figure of the Pharisee in the gospels is intended to convey). Ultimately, Christian healing originates in, and is sustained by, the love of the triune God that is offered to everyone, but can be appropriated only by those who willingly seek it and receive it or ‘take it in’ (Mt. 7:7-8; Jn. 1:12-13; Eph. 2:8-10)” (Johnson et al., 2020, p. 82). |

| “Centering prayer may hold promise as an alternative intervention for ameliorating chronic depression in Christian adults” (Knabb, 2012, p. 909). |

| “Given the psychological benefits of mindfulness and its connection to spirituality, it is not surprising that both therapists and Christian clients are attempting to incorporate it into counselling. Centering prayer, which is a form of Christian Devotion Meditation, provides an accommodative approach to managing worry for Christian clients” (Frederick & White, 2015, p. 850). |

| “CAM is becoming increasingly popular among contemporary North Americans, and it is therefore important for pastoral care providers to be somewhat knowledgeable about it. However, there are many areas of confusion and misunderstanding surrounding CAM. There are concerns about its efficacy, scientific basis, and spiritual roots. There are also economic, political, and ideological agendas associated with it. Consequently, CAM requires careful evaluation from both scientific and spiritual/religious perspectives. Furthermore, understanding some of the reasons for its popularity may help shape a pastoral response” (Warren, 2018, p. 22). |

| “He claims that the subtle energy (any force that exists outside known space-time and is unknown to science) characteristic of many alternative therapies, such as acupuncture and homeopathy, is ‘really the action of personal, demonic spirits.’ New Testament teaching advises followers of Christ to be on guard against false demonic signs and wonders” (Warren, 2018, p. 26). |

| “Many physiotherapists use manipulation techniques similar to those of chiropractors, many chiropractors now advise home exercise, and many fitness classes use stretches similar to those of yoga. Our approach needs to be nuanced. I agree that we should not simply ‘baptize’ CAM therapies with Christian language; however, it is difficult to ascertain at what point and in which situations certain practices lose their religious association. For example, I suspect that many, but not all, chiropractic and mindfulness therapies are disconnected from their spiritual roots. It is also difficult, and perhaps unwise, to prescribe a ‘dos and don’ts’ list; we need to rely on our professional and spiritual intuition in each individual case” (Warren, 2018, p. 26). |

| “A Christian might ask, ‘Does it serve Christian aims (e.g., to glorify God, act as revelation, develop and/or heal his creation, further his kingdom) or foster humanistic/New Age beliefs?’ Brown (2013, p. 159) suggests that churches may avoid teaching on CAM for fear of offending supporters who like CAM, but she is perhaps overly cynical in this regard. Regardless, given the popularity of CAM, education is essential” (Warren, 2018, p. 28). |

| “Similarly, MBCT’s mindful postures of accepting and allowing can be reinterpreted within a Christian perspective to mean surrendering to God’s will—‘letting go and letting God’” (Rosales & Tan, 2017, p. 80). |

| “Basic mindfulness tenets are actually consistent with Christian values” (Hoover, 2018, p. 249). |

| “Focusing on the examples of yoga and mindfulness, many such programs are framed as secular or universal, yet are deeply entwined with Hindu, Buddhist, and/or other religious beliefs, practices, and communities” (Brown, 2019, p. 142). |

| “Buddhist mindfulness meditation is an insight meditation, helping practitioners to better understand the ‘three marks of existence’ . . . whereas Christian meditative practices are about cultivating a deeper relationship with God, based on Christians’ union with Christ” (Knabb & Bates, 2020, p. 24). |

| “At this point, then, the literature on the psychology of Christian practices is still in its infancy” (Knabb & Bates, 2020, p. 37). |

| “Though hatha yoga is traditionally believed to be the ur-system of modern postural yoga, equating them does not account for the historical sources. Posture only became prominent in modern yoga in the early twentieth century as the result of the dialogical exchanges between Indian reformers and Americans and Europeans interested in health and fitness. Postural yoga’s sources include British military calisthenics, modern medicine, and the physical culture of European gymnasts, body builders, martial experts, and contortionists” (Jain, 2012, p. 7). |

| “Proponents of Christian Yoga argue that yoga itself is not a religion, but a universal set of techniques that can be used to strengthen a Christian’s relationship with Christ” (Jain, 2012, p. 6). |

| “Meanwhile, medical structures do afford space to certain religious traditions and practices: first, generic spirituality that purports to encompass all spiritual traditions though excluding particular theological claims about the nature of God, the self, and salvation; and second, Eastern religious practices such as yoga or mindfulness meditation that are framed as nonreligious despite roots in and ongoing ties to religion” (Brown, 2019, p. 141). |

| “One population that often has trepidations about mindfulness is conservative Christians. The Buddhist roots of mindfulness give them pause. Societal associations of the New Age movement with mindfulness sometimes leave them wondering if they are experiencing a form of ‘proselytizing’ in therapy as well. One way to respond to these concerns is for therapists to adapt these strategies to be more culturally sensitive to the client’s faith. A small Christian literature adapting mindfulness to Christian concerns is emerging . . . However, few resources exist showing clinicians how to specifically modify mindfulness meditations in a practical sense to incorporate a Christian worldview. Such adaptations likely would reduce the Buddhist and New Age associations for the meditations, make them consistent with a Christian worldview, and enhance their acceptability to the conservative Christian client” (Garzon & Ford, 2016, p. 263). |

| “For some conservative Christians, even Christian-adapted mindfulness may be too concerning because of cautiousness with any form of meditation. The Bible has many passages specifically encouraging meditation (See Psalm 1, Psalm 119, and Joshua 1, for example) so highlighting these Scriptures for such a client may be useful. Over the centuries, the Christian tradition has developed many ways to meditate on Scripture and commune with God . . . Clarifying this rich contemplative history and, when necessary, starting with these clearly identifiable Christian meditation forms may reduce general concerns about meditation and potential Eastern religious influences . . . Once the client is more comfortable with meditation, she may be more open to adapted mindfulness strategies” (Garzon & Ford, 2016, p. 267). |

| “Our purpose in this article is not to attack empirically supported mindfulness, but rather to supply therapists with practical scripts and information on how to accommodate mindfulness to conservative Christian client concerns . . . Rather, we hope that our ideas will stimulate the creation of further adapted meditations and, equally important, research into the impact of such methods” (Garzon & Ford, 2016, p. 267). |

| “The phenomenon of Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) is the ‘offspring’ of an unlikely ‘mating’ of rock and roll youth culture with the Jesus Movement of the 1960s-1970s. Older Christians objected that rock music, and especially loud drums and electric guitars, are inherently evil. The founder of Sparrow Records, Billy Ray Hearn, notes a pattern: ‘When something new comes along, the church usually rejects it; then they tolerate it; then it becomes acceptable; and, finally, it becomes traditional.’ Churches initially viewed Christian fiction, Christian music, and Christian yoga with suspicion, and Christians who wanted to participate had to justify their choices. Over time, participation was normalized” (Brown, 2018, p. 663). |

| “Is Christian yoga comparable to Christian fiction, Christian music, and Christian aerobics? All of these movements are appealing for similar reasons: they invite experiential, physically engaged and/or emotionally rich encounters with Got. They each reflect a belief-centered understanding of religion, which breeds confidence that meanings can be transformed by emptying and refilling neutral containers with Christian linguistic content, much like substituting ingredients in a recipe. This article contends that, despite these similarities, Christian yoga is more of a stretch theologically and culturally, myopic about the potential for practices to change beliefs, and prone to charges of cultural appropriation and cultural imperialism” (Brown, 2018, p. 664). |

| “Certain Hindu yoga proponents express an experiential view of religion based on metaphysical assumptions of how practices change beliefs. The Hindu American Foundation argues that “even when Yoga is practiced solely as exercise, it cannot be completely delinked from its Hindu roots” because āsanas, or postures, have ‘psycho-spiritual effects’” (Brown, 2018, p. 664). |

| “Doctrinal interpretations of religion notwithstanding, few Christian commentators argue that yoga is a purely physical practice. What they disagree over is whether yoga spirituality is antagonistic or complementary to Christianity” (Brown, 2018, p. 666). |

| “Evangelicals lack unified theological authority structures. Individuals who object to yoga cite at least one of two reasons. First, they worry about ‘idolatry’—prayer to or worship of gods other than Yahweh, contrary to the Bible’s first commandment: ‘You shall have no other gods before me.’ The Old Testament cautions against emulating how other cultures petition their gods: ‘You must not worship the LORD your God in their way.’ The New Testament forbids reverencing images of ‘birds and animals and reptiles.’ Christian critics worry that Sūrya Namaskāra developed as a prayer to the solar deity, Surya, and that many postures emulate animals associated with divine beings. Evangelical Marcia Montenegro argues that “‘Christian Yoga’ is an oxymoron . . . Just as there is no Christian Ouija board and no Christian astrology, so there is no Christian yoga that is either truly Yoga or truly Christian” (Brown, 2018, p. 667). |

| “Yoga misappropriated by naive westerners can be traced back to Hindu spirits who are not fooled by a little revamping. They’ve got the serial number and title deed, so to speak. They’ll get back in their vehicle while you’re driving it. By this logic, Christians do not own yoga and have no right to remove religion from or repurpose yoga as Christian. Nevertheless, Christian yoga is on the rise” (Brown, 2018, p. 668). |

| “Christians may turn to yoga to fill lacunae in Christian traditions—which they perceive as overly intellectual, uninteresting, or body-denying, or as needing to be enriched by insights from other religions. But, worried by non-Christian roots, they Christianize these practices. Father Thomas Ryan, director of the Paulist North American Office for Ecumenical Interfaith Relations, is a certified Kripalu yoga instructor who envisions ‘yoga prayer’ sacramentally as a way to ‘pray with your whole body.’ Ryan interprets yoga as superior to Christian ascetic disciplines or the valorization of physical suffering as sanctifying the spirit; in his view, yoga reveals that ‘salvation doesn’t mean getting out of this skin, [but] rather being transfigured and glorified in it.’ Evangelicals—aptly characterized by the historian Mark Noll as culturally adaptive, biblically experiential Christians—replace non-Christian with Christian language and religion” (Brown, 2018, p. 669). |

| “Evangelical adaptations of yoga and the creation of yoga alternatives presume that practices can be Christianized through linguistic substitution” (Brown, 2018, p. 670). |

| “By evangelical logic, if someone dedicates a practice to Jesus, it is by definition Christian” (Brown, 2018, p. 670). |

| “The churches are emptying; the yoga centers are full” (Brown, 2018, p. 673). |

| “Modern evangelicals are better educated than their Fundamentalist predecessors, but many lack training for yoga culture wars. Evangelicals are poorly equipped to engage reflectively with popular culture because most lack interest in rigorous historical and theological study that could pinpoint continuities and discontinuities with Christian traditions” (Brown, 2018, p. 681). |

| “Strategies of manipulative body and healing energy practices focus on interacting with fields within the body that are thought to promote wellness, including meridians and chakras. Meridians are energy pathways that connect to the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system and regulate physiological function and balance” (Kanegan & Worely, 2018, p. 17). |

| “Yogic manipulation of subtle energy could function as a healing agent” (Jain, 2014, 442). |

| “Energy medicine: practices that rely on energy fields that are thought to surround the body as well as bio-electromagnetic-based therapies; for example, therapeutic touch, Reiki, tai chi, qi-gong” (Warren, 2018, p. 23). |

| “For a brief review, metaphysical religion can be defined as any religion that deemphasizes ‘personal conceptions of the divine,’ stresses the ‘correspondence between supernatural and natural realms,’ and underscores the ‘manipulability of spiritual power’ . . . New-age spirituality (actually not new, but a repackaging of eastern mysticism and occult practices) is a common example. Such religions claim that the divine is within us and evil is not real. They usually believe in a universal life force or vital/positive energy, and can be categorized as pantheistic, monistic or holistic—‘all is one,’ ‘the true you is the ocean.’ This contrasts with Christianity, which places a clear distinction between God and creation and emphasizes the Holy Spirit as a personal being, not an impersonal force” (Warren, 2018, p. 25). |

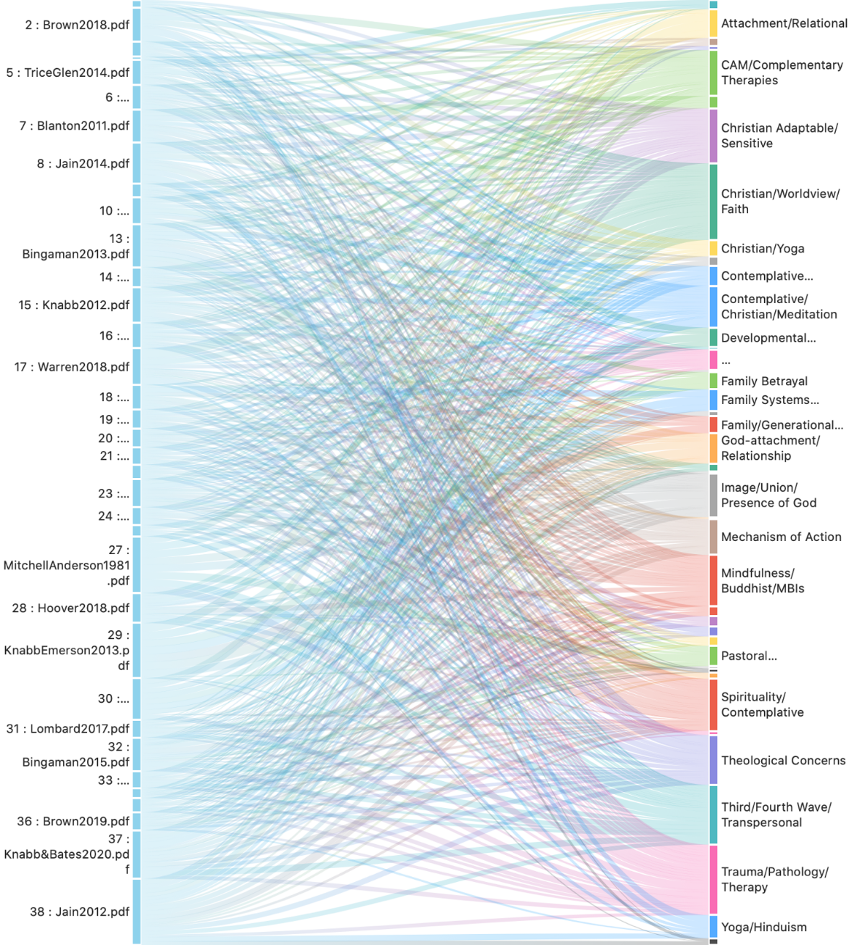

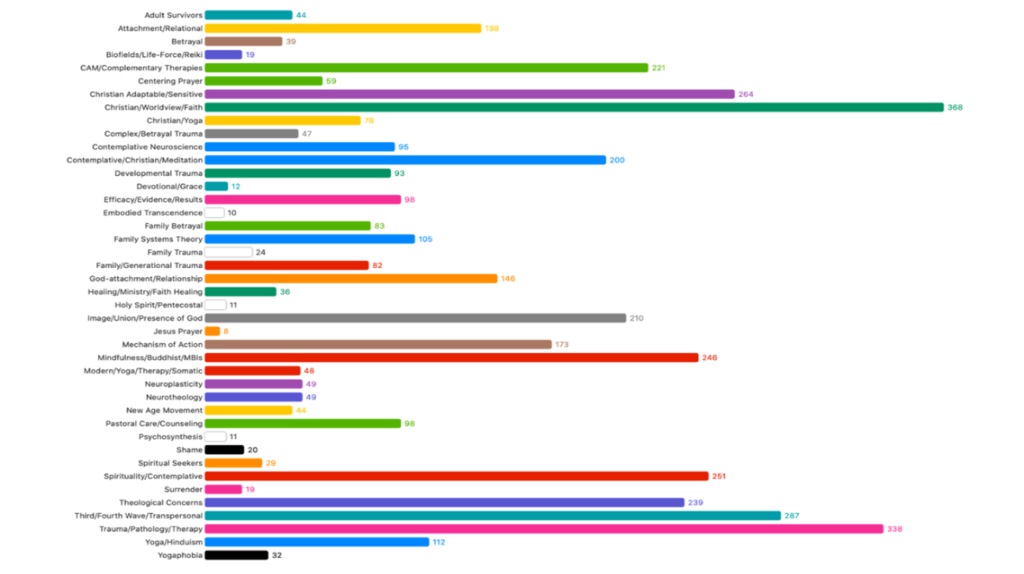

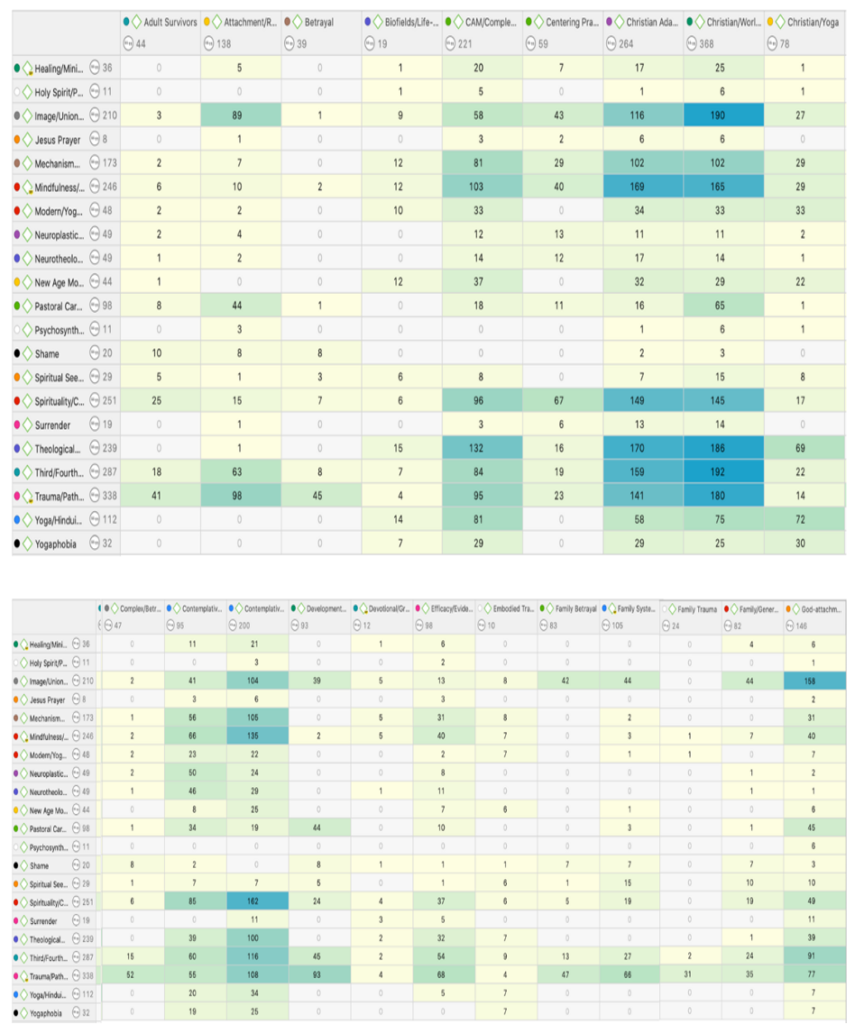

| Bingaman (2011) | 23 | Neurotheology recognizes contemplative Christian spiritual practices as catalytic for calming an overwhelmed amygdala. | C |

| Bingaman (2013) | 13 | Neurotheology urges pastoral counselors to integrate contemplative practices due to their ability to rewire the human brain. | D |

| Bingaman (2015) | 32 | Advances in neuroscience validate integration of meditation into pastoral care work to help heal trauma and stress. | B |

| Blanton (2011) | 7 | Mindfulness practices (yoga, meditation, centering prayer) have been practiced by many religions for thousands of years. | D |

| Brown (2018) | 2 | Yoga cannot be Christianized because it is a theological oxymoron like Christian-Hinduism. | D |

| Brown (2019) | 36 | Christian healing and spirituality are being influenced by yoga and mindfulness practices which are rooted in other religions. | D |

| Delker et al. (2018) | 10 | FB predicated clinically significant increases in traumatic stress in adults who experienced childhood trauma. | B |

| Doehring (2019) | 34 | Pastoral counselors can adopt third- and fourth-wave spiritual interventions without Christian adaption. | D |

Doucet & Rovers (2010) | 30 | Spiritual and religious interventions used by pastoral practitioners can catalyze healing in trauma survivors. | B |

| Ford & Garzon (2017) | 21 | Christian-accommodated BT interventions can be as or more effective than secular, and useful in pastoral and lay-ministry. | A |

Frederick & White (2015) | 16 | Surrender to God is the mechanism of action underlying Christian meditation which makes it distinct from mindfulness. | A |

| Garzon & Ford (2016) | 1 | The Bible encourages meditation, and research needs to address more information on how to adapted mindfulness for Christians. | B |

| Glenn (2014) | 5 | Pastoral counseling aids adult survivors of familial trauma integrate spirituality into the healing process. | B |

| Hathaway & Tan (2009) | 6 | Third-wave CBT practices can successfully be adapted to conservatively Christian clients creating increased effectiveness. | C |

| Heiden-Rootes et al. (2010) | 18 | Spiritual seeking can actually serve as a healthy way to differentiate from one’s family system according to FST. | B |

| Hoover (2018) | 28 | No irreconcilable differences exist between mindfulness and Christianity, and therefore Christians can adapt CTs. | C |

| Jain (2012) | 38 | Yoga has been defined by divergent terms for 3,000 years, and has been adopted by many religions throughout time. | B |

| Jain (2014) | 8 | Modern yoga cannot be quantified as essentially Hindu in origin, and it is a product of modern culture. | C |

| Jain (2017) | 25 | It is impossible to essentially quantify yoga or Christianity due to the elusive history of yoga. | C |

| Johnson et al. (2020) | 9 | The Christian purpose of meditation is different—and more important—than whether it produces results. | C |

| Jones et al. (2021) | 20 | Preliminary evidence that mindfulness can be Christian-adapted for conservative evangelical Christians for trauma. | A |

Kanegan & Worley (2018) | 4 | CTs have proven benefits that address symptoms of PTSD and help alleviate SUD struggles. | D |

| Knabb (2012) | 15 | Awakening the image of God is at the core of Christian contemplation, and suggests it shows basic effectiveness in trauma. | B |

| Knabb & Bates (2020) | 37 | Christians need to return to contemplative spiritual healing practices from their own lineage instead of utilizing mindfulness. | A |

| Knabb & Emerson (2013) | 29 | The grand narrative of Scripture illustrates an attachment relationship between God and his people exemplified in the fall. | B |

| Knabb, Johnson, et al. (2020) | 3 | The goal of Christian meditation is communion with God and others through union with Christ contrasting Buddhist mindfulness. | C |

| Knabb, Vazquez, et al. (2020) | 19 | Christian-sensitive alternatives to mindfulness allow Christians to access the benefits of meditation with theological integrity. | A |

| Knabb et al. (2019) | 35 | Christian meditation utilizes a similar mechanism of action as mindfulness; namely, surrender and humble detachment. | A |

| Knabb et al. (2021) | 22 | Christian meditation is as, or more, effective than Buddhist and we can use Christian-sensitive or distinct practices. | B |

| Lombard (2017) | 31 | Psychosynthesis and transpersonal psychology fourth wave concepts can successfully be integrated into pastoral counseling. | B |

| Mitchell & Anderson (1981) | 27 | Pastoral counseling should address the Family Systems Theory of leaving and cleaving based on the biblical mandate to do so. | C |

| Rosales & Tan (2017) | 24 | Mindfulness in MBCT can be Christian-adapted by reinterpreting it to mean focusing on God’s will. | D |

| Rubinart et al. (2017) | 14 | Christian spirituality helps heal interpersonal neurobiology and attachment to both others and God. | A |

Wang & Tan (2016) | 33 | It is clinically advised that Christian-adaption and contemplative Christian practices be incorporated into third-wave treatments. | C |

| Warren (2018) | 17 | Pastors should be aware of CTs, and educate congregants about its efficacy, appropriateness, and spiritual roots. | B |

Note. Meta-synthesis study (N = 35).CTs = complementary therapies, MBCT = mindfulness based cognitive therapy, FST = family systems theory.

a This number corresponds to the coding number assigned

Meta-Synthesis: Articles for Inclusion

Authors | Inclusion Topical Criteria | Type of Article | Theme |

Bingaman (2011) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Bingaman (2013) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Bingaman (2015) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Third Wave Pastoral Counseling |

| Blanton (2011) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Brown (2018) | Healing Ministry & CTs (Seminal/Specialty) | Expert Perspective | Christian Yoga |

| Brown (2019) | Healing Ministry & CTs (Seminal/Specialty) | Expert Perspective | Christian Yoga & Healing |

| Delker et al. (2018) | Familial Trauma & Healing (Seminal/Specialty) | Research Study | Family Betrayal (FB) & Healing |

| Doehring (2019) | All three topical criteria met | Case Study | Pastoral Counseling |

| Doucet & Rovers (2010) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Spirituality in Trauma Healing |

| Ford & Garzon (2017) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian Accommodative CTs |

| Frederick & White (2015) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian CTs & Trauma |

| Garzon & Ford (2016) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Glenn (2014) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling |

| Hathaway & Tan (2009) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Religious MBCT |

| Heiden-Rootes et al. (2010) | All Three Topical Criteria Met | Research Study | Spiritual Seeking and FST |

| Hoover (2018) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Christian-adapted CTs |

| Jain (2012) | Healing Ministry & CTs (Seminal/Specialty) | Expert Perspective | Christian Yoga |

Jain (2014) | Healing Ministry & CTs (Seminal/Specialty) | Expert Perspective | Christian Yoga |

| Jain (2017) | Healing Ministry & CTs (Seminal/Specialty) | Expert Perspective | Christian Yoga |

| Johnson et al. (2020) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian Indigenous Practices |

| Jones et al. (2021) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian Accommodative CTs |

| Kanegan & Worley (2018) | CTs and Familial Trauma (Seminal/Specialty) | Clinical Applications | SUD and CAM |

| Knabb (2012) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Knabb & Bates (2020) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Christian CTs & Trauma |

| Knabb & Emerson (2013) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Scripture & Attachment Theory |

| Knabb, Johnson, et al. (2020) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Knabb, Vazquez, et al. (2020) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian Meditation for Healing |

| Knabb et al. (2019) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian CTs & Trauma |

| Knabb et al. (2021) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Christian Meditation for Trauma |

| Lombard (2017) | All three topical criteria met | Case Study | Christian Fourth Wave |

| Mitchell & Anderson (1981) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling |

| Rosales & Tan (2017) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Christian MBCT |

| Rubinart et al. (2017) | All three topical criteria met | Research Study | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Wang & Tan (2016) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Christian Approach to DBT |

| Warren (2018) | All three topical criteria met | Clinical Applications | Pastoral Counseling & CTs |

| Note. Meta-synthesis study (N = 35). |

This is copyrighted material that may not be reproduced with written permission by the author.

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

Do you want to learn more about Christian complementary therapies? Check out my course!

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment