Related Literature

An abundance of literature exists regarding the use of CTs for healing trauma (Gulden & Jennings, 2016; Hull et al., 2015; Mohi-Ud-Din & Pandey, 2018; Pence et al., 2014; Sears & Chard, 2016). There is an explicit conversation regarding the theological suitability of CTs for Christians (Brown, 2018; Garzon & Ford, 2016; Jain, 2012, 2014, 2017). There is a straightforward conversation regarding family trauma as a subset of C-PTSD (Hann-Morison, 2012). The literature appears to be lacking almost any conversation regarding Christian-adaptable complementary therapies for healing family trauma (Coe et al., 2018; Foroughe & Muller, 2014; Goldner et al., 2019; Shevlin et al., 2017; Stephens & Aparicio, 2017). The Christian church is in dire need of a clear consensus regarding the role of CTs in the context of family trauma.

Synthesis

Familial trauma’s roots begin in attachment theory founded by Ainsworth and Bowlby (1991). This theory suggests that individuals remain on a developmental pathway that impacts personality development based on the security of the initial bonds formed with primary caregivers. This ties in to the unfolding of that system over the child’s lifetime. This family-of-origin dysfunction carries into the overarching field of marriage and family therapy (MFT; Tan, 2011). This theory suggests that dysfunctional and traumatized families project their unconscious pain onto other members in predictable triangulation patterns, parentification, scapegoating, and enmeshment. When families maladaptively move through FST, developmental trauma disorder (DTD) can ensue (Willis et al., 2020).

DTD is an emerging diagnostic category promoted primarily by Van der Kolk (2005). DTD is a proposed diagnosis that extends beyond family systems and attachment theories to address a cluster of seemingly unrelated psychopathology rooted in chronic childhood trauma (Van der Kolk & Courtois, 2005). It is a more defined subset of complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD). Glück et al. (2016) further differentiate this subset of C-PTSD within the context of childhood trauma. C-PTSD is a forming diagnosis that differentiates the symptomology of trauma that emerges in interpersonal relationships (Herman, 2012). Finally, betrayal trauma is a further emerging subset of family trauma with roots in attachment and relationship betrayals (Gomez et al., 2016). Betrayal trauma and C-PTSD symptoms are common in adult survivors of familial trauma who often go undetected until relational and marital chaos bring them to therapy as adults (Mandeville, 2021). The trauma of their upbringing often lives on in their parenting and marriages in the form of relational instability, affect regulation issues, and insecure attachment patterns (Heller & LaPiere, 2012). Survivors are often misdiagnosed with a myriad of seemingly unrelated personality disorders when the issue of family trauma goes overlooked (Heller & LaPiere, 2012).

Trauma formed in the context of a relationship, specifically in one’s initial attachment bonds, must therefore be healed in the context of the relationship (Gingrich, 2013). Furthermore, recovery often gets impeded by a failure to acknowledge the interrelatedness symptoms, which often escalate under the emotional abuse still ensuing from the family of origin (J. D. Ford et al., 2018; Herman, 2012). Integration of somatic and complementary therapies (CT) such as yoga, meditation, and mindfulness into the treatment process proves superior to talk-only interventions (Fay & Germer, 2017; Malchiodi, 2012). This phenomenon is represented by the third wave of cognitive-behavioral therapies, which integrate mindfulness and meditation into the treatment process (Tan, 2011).

This integration poses serious theological questions to Christians due to the allegations of Buddhist and Hindu origins of the practices (Brown, 2013, 2018). Pastors are faced with the issue of helping these hurting families and survivors in a biblically sound manner (Rosales & Tan, 2016, 2017; Wang & Tan, 2016). Pastoral counseling and lay-ministry are a much-needed integration as a CT modality itself (Tan, 2016). More than ever, pastoral counselors are needed to expand the bandwidth of healing families by making lay counseling ministries more accessible (Tan, 2016). In recent studies, Christian-adapting CTs and lay counseling have been proven effective (Garzon & Ford, 2016). In a world fraught with emotional pain rooted in one’s family-of-origin, pastoral and lay-ministry counselors need to lead as forerunners in the arena of developing Christian-adapted CTs for familial trauma (Stone, 1994). The emerging field of neuroscience provides insight into a quickly evolving intersection of Christian spirituality and pastoral counseling (Bingaman, 2013).

Existing and Developing Literature

Neurobiology of Trauma

Uhernik (2017) is a leading advocate for the use of CTs in treating the neurobiology of trauma. She contended for the extensive use of CTs as a central part of the trauma healing process including bioenergetic healing, yoga therapy, mindfulness, meditation, neurofeedback, and creative expression as non-verbal methods of healing. Uhernik (2017) proposed that these methods are superior to talk-only therapies, which fail to address the nervous system dysregulation common in trauma survivors. Healing a wounded brain happens through interpersonal relationships. Mother-child attachment disruptions are indicated in brain development setbacks. Clients suffering from trauma are often stuck in fight or flight and need help calming the amygdala. She advocated for the screening of attachment trauma. Bottom-up approaches to healing trauma can better help calm the nervous system (Uhernik, 2017).

According to Briere and Scott (2015), trauma is defined as a highly upsetting event that overwhelms a person’s ability to cope and produces maladaptive psychological responses. Around fifty percent of Americans will experience trauma at some point in their lives. Trauma can include child abuse, mass violence, natural disasters, fires, accidents, rape, assault, domestic violence, human trafficking, torture, and war. Traumas such as natural disasters, fires, or accidents are considered impersonal, whereas traumas such as assault, child abuse, and domestic violence are considered interpersonal. Collective traumas create an additional set of symptoms that increase the risk of revictimization in survivors. Adult survivors of complex trauma might have symptoms that last well into adulthood (Briere & Scott, 2015).

Briere and Scott (2015) described a hyperreactive nervous system as a result of trauma. It perpetuates dysfunction in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Emotions such as anger, shame, and guilt are common in trauma survivors. They also focus on a particular type of trauma that is interpersonal, such as childhood abuse and neglect. These survivors experience usual symptoms like mood issues, cognitive distortions, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Due to the additional insult of the interpersonal nature of the events, they also often experience the effects of parent-child attachment ruptures. Symptoms include affecting regulation issues, identity issues, reduced capacity for interpersonal relations, and victimization, which lends itself to more personality-disorder-like difficulties in survivors (Briere & Scott, 2015).

Furthermore, Briere and Scott (2015) link dissociative symptoms to childhood neglect and insecure attachment bonds between parent and child. Insecure attachment can be a sign of developmental neglect and abuse. Somatization is a common symptom in childhood abuse survivors. This dynamic is a phenomenon where they experience physical pains not linked to apparent medical concerns. A term used for this type of compounding stress which occurs over time is complex post-traumatic stress. This dynamic arises from intense, long-term, interpersonal trauma that often begins in early development (Briere & Scott, 2015). This trauma classification also creates symptoms such as trouble with boundaries, interpersonal struggles, and affect dysregulation. These adult survivors often find themselves in chaotic and maladaptive relationships. These struggles are attributed to attachment issues in childhood. In severe cases, this can morph into borderline personality disorder (BPD). BPD is thought to arise in enmeshed maternal bonding issues. This diagnosis often receives substantial stigma in the medical community instead of compassion for its etymology (Briere & Scott, 2015).

Briere and Scott (2015) recommend meditation and mindfulness in some instances of trauma recovery in conjunction with psychotherapy. In some instances, pharmacology is indicated. Mindfulness can provide additional therapeutic relief that differs from the impact of psychotherapy. In some instances, mindfulness is contraindicated, such as when the survivor struggles with psychosis, dissociation, or destabilization. Briere and Scott (2015) described the emerging waves of behavioral therapy. The first and second waves focused on remedying cognitive distortions. The third and fourth focus on the integration of spirituality and mindfulness into the therapy process. The integration of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) and mindfulness mark the third wave of dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT). This modality is especially useful in working with BPD clients. Although mindfulness is indicated for many trauma survivors, it is by no means a replacement for psychotherapy (Briere & Scott, 2015).

Furthermore, Brier and Scott (2015) stated there is mindfulness training in therapists and how to teach the modality to survivors best. Often, meditation teachers have been practicing for many years. Thus, therapists who have mindfulness training might incorporate essential aspects into the therapy relationship. Of primary importance is the scope of meditation and psychotherapy practitioners (Briere & Scott, 2015).

Complex Trauma

According to Cloitre et al. (2010), complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) is an emerging subset of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which includes additional features such as issues of self-organization, affective dysregulation, negative self-concept, and interpersonal problems. It is associated with more significant with greater impairment than PTSD. They correlated childhood trauma with a distinctive C-PTSD diagnosis. Glück et al. (2016) found the specificity of childhood trauma in the PTSD diagnosis to reduce common comorbidities. Becker-Weidman and Hughes (2008) reported that children who experience complex trauma are at increased risk for developing psychopathic personality disorders, social rejection, anxiety, SUD, and antisocial personality disorder. They require treatment that addresses self-regulation, interpersonal skills, attachment, somatization, regulation, dissociation, behavior control, attention, executive function, and self-concept issues (Becker-Weidman & Hughes, 2008). Herman (2012) likewise advocated for the inclusion of C-PTSD as a distinctive diagnostic category. The distinction is both theoretically and clinically vital. Herman outlined the specificity of symptoms that often presents as unrelated psychiatric complaints. When left improperly diagnosed, treatment becomes cumbersome and ineffective.

Courtois (2004) defines complex trauma as a specific subset that occurs cumulatively in a relational context. Complex trauma rooted in family abuse tends to be especially pervasive. Dorahy et al. (2013) described C-PTSD as a relational disorder with roots in relational trauma that creates relational disconnects. Shame and dissociation are primary contributors to relational chaos. C-PTSD can lead to an inability to form and maintain family and social ties. These individuals redirect relational conflict inward toward the self (Dorahy et al., 2013). Van Nieuwenhove and Meganck (2019) explained feelings of mistrust and suspicion of others familiar to those with C-PTSD. These individuals feel more worthy of abuse and pan and tend toward beliefs that one is worthless and unlovable. They found a specific subset of C-PTSD that occurs during development and attachment. This dynamic causes abuse-related schemas, translating into interpersonal function issues related to intimacy, trust, and communication

(Van Nieuwenhove & Meganck, 2019).

Christian Counseling on C-PTSD. Gingrich (2013) described complex PTSD

(C-PTSD) as symptoms rooted in interpersonal trauma such as affect dysregulation, dissociation, self and perpetrator distortions, relationship chaos, physical complaints, and systems of meaning struggles. The three phases of treatment indicated include safety and stabilization, trauma processing, and consolidation and resolution. Clients need help learning safety in relationships. They need to build skills in understanding who is safe and who is unsafe. Gingrich (2013) discussed dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which clients struggle with multiple personalities. She addressed important considerations for Christian counselors when working with such individuals, additional sensitivity to Christian concern, and the role of God in the trauma.

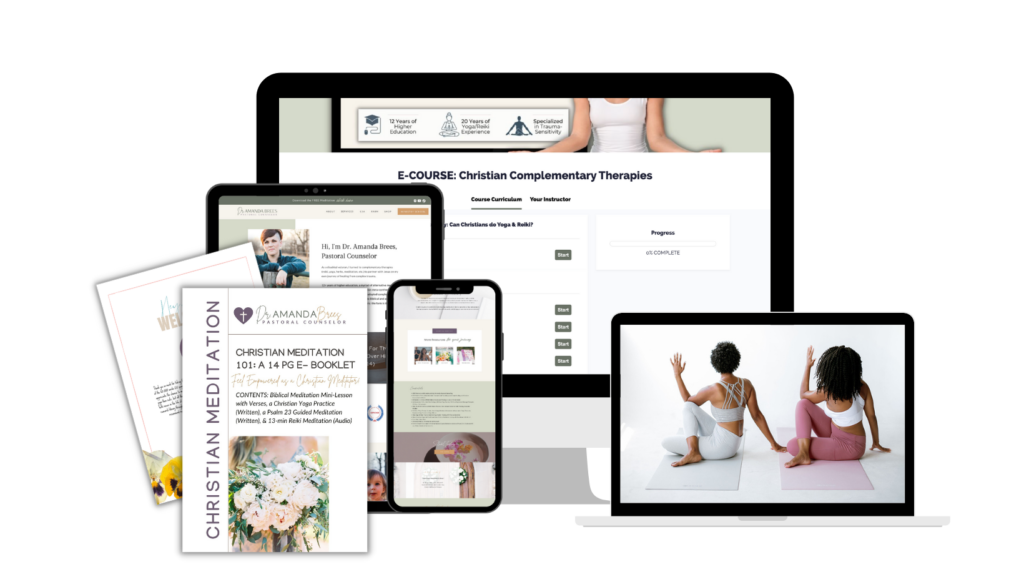

Want to learn more about Christian meditation?

Take the e-course!

References

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment