Attachment-Rooted Familial Substance Use Disorder. Substance use disorder (SUD) is a primary culprit of familial trauma often rooted in attachment dysfunction. Rasmussen et al. (2018) found that the prevention of childhood trauma can reduce SUD. Conversely, SUD clients should also get screened for childhood trauma and then treated with proper attachment-rooted interventions to increase recovery rates. Fletcher et al. (2015) asserted that substance abuse had become a public health crisis with very high costs to society. They further asserted the failure of current treatment models to address the problem at its root cause adequately. Family chaos ensues when the addicted partner has a primary attachment bond with a substance instead of their spouse. Healing can be expedited through a 12-step program which can act as a transitionary attachment figure in recovery. Stephens and Arpicio (2017) described the strife and trauma of the marginalized of society who suffer from foster care and familial SUD intergenerational patterns. They advocate for the use of faith-based communities as part of a more extensive policy reform that addresses the underlying attachment needs of these mothers.

Lange-Altman et al. (2017) described the co-occurrence of SUD and PTSD as standard. They advocate for the integration of 12-step models with evidence-based interventions. Schindler (2019) described SUD as an attempt to compensate for lacking attachment security and suggested that continued substance use impedes one’s ability to form meaningful relationships. Often, users present with very insecure attachment patterns. Belmontes (2018) discussed the role family systems play in the recovery process. Family systems can impede recovery efforts due to the fact they have revolved their rules around the addict. Alternatively, the system may have an alcoholic culture that prohibits them from realizing there is a problem. Therefore, the family system must be engaged in the process of recovery (Belmontes, 2018). Ulaş and Ekşi (2019) described a lack of research regarding family systems’ roles in recovery. Their findings suggested that family systems therapy helped decrease drug use. They suggested family therapy be the preferred treatment intervention for SUD. O’Farrel et al. (2010) also asserted that family involvement improves treatment outcomes for addiction recovery.

Family Systems Theory

Tan (2011) described Murray Bowen as one of the modern forerunners of marriage and family therapy (MFT). MFT began in the 1940s and is considered the fourth force of therapy. Counseling as a ministry was informally acknowledged since the 1700s. Family therapies utilize techniques such as boundary setting, reframing, and genograms as therapeutic tools. Murray Bowen was a Tennessee native who became a psychiatrist. His work with patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and their mothers resulted in his work on the differentiated self. It included the study of the autonomy of an individual in the context of a family system. Key concepts are differentiation of self, triangulation, and multigenerational transmission (Tan, 2011). Bowen’s most well-known work is Theory in the Practice of Psychotherapy (Bowen, 1976). Salvador Minuchin (1974) was another pioneer of family systems theory who also contributed to the field.

Tan (2011) stated that Bowen believed family members live connected to their more extensive system and are, therefore, susceptible to emotional fusion due to their reaction to the unit’s struggles. Differentiation of self has to do with a person’s ability to separate from their system. Triangulation happens when one person brings a third person into a conflict; for example, a married couple might pull in their teenage daughter to create a two-against-one effect instead of dealing with their marital issues. Often, the third party may act out in protest. Low levels of differentiation can be passed down through generations, especially in marriage. MFT avoids scapegoating or placing all the issues of the family onto an individual member (Tan, 2011).

Differentiation. A key concept of family systems theory (FST) is the issue of differentiation. Willis et al. (2020) defined differentiation similarly to Bowen by calling it the dance of intimacy and autonomy in relationships. Inadequate levels of differentiation lead to higher levels of stress, anxiety, physical health problems, and marital stress. Triangles make up the basics of an emotional system in a group or family system. Willis et al. failed to support Bowen’s theoretical argument regarding stress as a moderator between differentiation and outcomes of interpersonal issues. Their findings found that stress is the predictor of differentiation and anxiety (Willis et al., 2020).

Emotional Overinvolvement and Enmeshment. A related concept to differentiation and triangulation is emotional overinvolvement. Khafi et al. (2015) defined emotional overinvolvement (EOI) as excessive parental worry, concern, praise, or self-sacrifice that constitutes an enmeshed parent-child dyad. Enmeshment or EOI occurs when the boundaries between parent-child subsystems become too diffuse to the point the parent uses the child to meet their psychological needs (Kafi & Yates, 2015). Coe et al. (2018) pointed to maternal relationship instability as a significant risk factor for children’s developmental success. Minuchin (1974) addressed the role of boundaries in FST that exist on a continuum from enmeshment to cohesion. Cohesion exists when members of a family or group system are allowed ample autonomy, whereas enmeshment exists when a lack of warmth, empathy and emotional support exists when a member demonstrates autonomy. Minuchin (1974) described enmeshed families as those who become emotionally entangled with each other.

Parentification. Love and Robertson (1991) described the emotional bond of infant-mother as very strong, therefore needing considerable offset to keep it within reasonable boundaries. It is the mother’s job to provide a secure attachment base for the child. Hann-Morrison (2012) described disengagement or estrangement from one’s family of origin as an equally destructive emotional reality. Love and Shukin (2001) drew out theories such as the emotional incest theory, where children become parentified by parents when they get forced to assume partnered roles in the parental dyad due to familial traumas. They described the shared unconscious drive of individuals to recreate the maladaptive love they were attuned to as a child in their adult relationships regardless of how destructive it might have been. Coe et al. (2018) stated that traditionally, individuals are given adequate psychological support to differentiate from their birth family with ease. Enmeshed family systems discourage this natural differentiation process as a narcissistic parenting tactic that punishes efforts to differentiate.

Minuchin (1974) was a key founder of the idea of a parentified child. Earley and Cushway (2002) describe the phenomenon as a child taking on the role of a parent in the family system. This dynamic is a role reversal where the child acts as a parent to the parent. These children will often act as codependent enablers or scapegoats in a substance-using system. Family systems theory (FST) states that children are at risk of parental schizophrenia, divorce, poverty maternal mental illness, sexual abuse, and intrusive parenting styles. The key struggles these survivors have as adults involve their ability to handle being rejected and their role in relationships. These children are often prone to shame due to their inability to meet parental expectations. They also use splitting as a defense mechanism during interpersonal conflict and tend to adopt caretaking syndrome as adults. These adult survivors struggle with personality issues, interpersonal relationship chaos, and the stress of parenting (Earley & Cushway, 2002).

Hooper (2007) defined parentification as the intersection between attachment theory and FST. FST clarifies the context where the parentification takes place. Attachment theory clarifies the process of parentification in the context of the parental attachment bond. Adult survivors of parentification struggle with relationship instability, attachment difficulty, and poor differentiation from the birth family. Risk factors for children include parental psychopathology, substance abuse, marital discord, and mental illness. These issues make it impossible for a parent to provide a secure base for a child. The author advocates for integrating attachment and family systems theories to best help adult survivors of parentification (Hooper, 2007). Haxhe (2016) described Boszormenyi-Nagy’s description of the scapegoated parentified child, perfect child, and caregiving child. Parentification includes an emotional component different than simply delegating essential chores to a child.

Rejection Sensitivity. Goldner et al. (2019) described rejection sensitivity as a phenomenon rooted in insecure attachment wounds that lend themselves to increased awareness of rejection in the face of relationships. It is a defense mechanism that undermines the ability to have intimate relationships. This sensitivity can be born in the context of parentification and enmeshment.

Codependency. Prest et al. (1998) advocated for Bowen’s FST as the appropriate container for understanding the development of codependency. Differentiation issues in childhood lend themselves to difficulty establishing marital relationships. The patterns of the birth family are maladaptive in the face of chronic alcoholism. In FST, codependency coexists with fusion, enmeshment, low individuation, and triangulation among members in a quest to resolve common issues of identity and intimacy in the system. Codependence can be seen as a method for coping with an alcoholic family system (Prest et al., 1998).

Family Scapegoating Abuse. According to Mandeville (2021), toxic family systems can bully a single member as a way to scapegoat their problems. She terms this family scapegoating abuse (FSA). She proposed this theory to be an evolution based on Bowen’s Theory. This role involves the most vital member who can bear the burden of the family system in alignment with Leviticus 16:8-10. The family can go so far as to side with an ex-spouse in a divorce. The family creates smear campaigns against a single member to project their unconscious emotional dynamics. This issue often happens with parents diagnosed with bipolar or borderline personality disorder who split siblings and pit them against one another in alliances. The scapegoat gets painted as unlovable and worthy of the emotional abuse from the family system (Mandeville, 2021). This type of abuse is often not recognized by family courts. The system fails to recognize or acknowledge one’s professional accomplishments outside the system. They simply write the survivor off as having tricked or manipulated others instead of having profound accomplishments. Survivors suffer from disenfranchised grief that cannot be openly shared with others and adequately mourned. Survivors often end up codependent with addicts. The dyad with the most power in the family system will label them crazy and inform anyone who will listen that they are the victims of a defective child or child-in-law. Survivors may fawn in the face of conflict. They will struggle to create conflict and often tell others what they want to hear (Mandeville, 2021).

Research Gaps

A variety of seminal and emerging primary theorists and diagnostic classifications broadly encompass the multifaceted aspects of delineating the phenomenon of family trauma. Children who experience family trauma have less self-esteem and social competence (Forough & Muller, 2014). This study seeks to identify this subset of familial trauma further to hopefully advance understanding of the implications of this specific type of trauma.

This study would serve a few academic needs. First, it would offer clients and congregants direct access to the research findings of a vast body of research. This access would eliminate the appeal to authority dynamic and allow each Christian a chance to make informed decisions for themselves regarding the presence or the absence of CTs in their lives. It would eliminate the physician and pastor as gatekeepers for individuals and lay ministers deciding whether or not CTs are appropriate based on research and science in a container of faith.

It would also streamline assistance to many hurting families. Adult survivors of familial trauma would profoundly benefit from being highlighted in the research. Although it would be vital to help to hurt families, adult survivors would also get better included in ministering to families. These individuals might get treated for multiple psychiatric conditions as adults. They might struggle with relationship issues that seem resistant to traditional treatments. With access to lay ministers, help becomes more accessible. Needed barriers are overcome as more people have faster access to grounded theories and proper training.

Furthermore, the church would benefit from better being able to serve both hurting families and adult survivors. These adult survivors of familial trauma might be suffering from predictable symptoms of their developmental trauma. The enmeshment, parentification, and attainment failures they experienced as children can live on in their adult failures to create families. These survivors suffer from betrayal trauma in their families, and their response to trauma gets labeled as pathological. Not only is the survivor wounded by the trauma, but the fundamentalist view of marriage further shames these individuals into feeling like bad Christians.

This dynamic perpetuates a vicious cycle for adult survivors. It also fails to help the church reach its goal of supporting healthy families from a biblical standpoint. In today’s culture, a biblical approach to family life is needed more than ever. Perhaps pastors would be more effective in helping families find true healing if they stopped alienating these adult survivors and instead ministered to their broken hearts. This approach to healing families could help adult survivors stop the relational chaos that lives on inside them and form the biblical family God intended for them all along.

This study would practically inform trauma-focused Christian yoga, meditation, and Reiki practitioners as well. It would also inform Christian counselors and clinical counselors integrating CTs into their practice. The church could more effectively help to hurt families through a streamlined theory of Christian-adaptable CTs for family ministry. Once this theory becomes grounded, it could effectively position lay ministers and pastoral counselors in a strategic place between medical and church authorities and politics unrelated to CTs’ efficacy for family ministry. Identifying the need for religious accommodation strengthens the faith of believers who otherwise might feel alienated from faith communities. Those interested in CTs might overcome blocks to faith through shared values. The issue can effectively be removed from the authorities, and into the hands of the people. From there, they can marry the contents of the research with the voice of God alongside wise counsel in their own lives to arrive at biblical conclusions on the subject. This approach removes the intermediatory of a medical or pastoral authority figure between the people and God regarding whether CTs are appropriate.

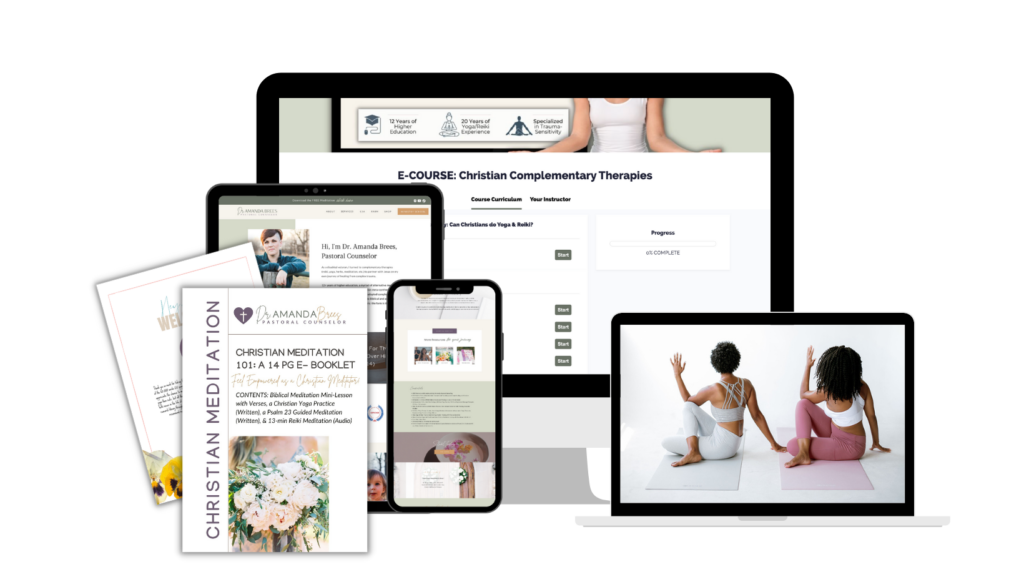

Do you want to learn more about using complementary therapies for family ministry?

Take the class!

References

Brees, Amanda Lynne, “The New Age of Christian Healing Ministry and Spirituality: A Meta-Synthesis Exploring the Efficacy of Christian-Adapted Complementary Therapies for Adult Survivors of Familial Trauma” (2021). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects. 3168.

https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/3168

+ show Comments

- Hide Comments

add a comment